Update #4: Cape Bird

On Saturday we arranged for a flight out to Cape Bird, perhaps my favorite place on Ross Island. Once again we packed into the 212 for a flight up and over the western flank of Mt. Erebus, with a dramatic drop down to the narrow beach at Cape Bird. We heard that the McMurdo pilots don’t really like flying out to Bird because of the precise maneuvering required to gain the pad without disturbing the birds at the colony. Our pilot wasn’t very happy about the winds, and had to do a bit of orbiting to find a way in to the pad. As we unloaded, we were very surprised to see a familiar, smiling face- New Zealand penguin biologist Kerry Barton was here in 2001 when we stayed in the hut, and here she was again. We rolled our gear down the beach in the Kiwi’s wheel barrow, and lugged everything up the stairs to the hut.

Bell 212 on the pad at McMurdo (left), and the Cape Bird hut (right).

The Cape Bird hut was constructed in the 1980s, following some earlier refuges that were built in the 1960s and 70s. This newest version is Ross Island’s version of a bed and breakfast- sleeping facilities for 8, a lovely kitchen with propane stove and freezer, central heat from a diesel-burning Preway stove, and best of all- huge front windows looking out over McMurdo Sound and the Ross Sea. Accommodations truly could not be more luxurious for a field camp, and we were pleased when the New Zealand Antarctic program granted us permission to stay there for a few days. We unpacked our field gear, and headed out immediately for the North Colony.

The spacious interior of the Cape Bird hut (left) and the ice front of the Bird Ice Cap (right).

The Cape Bird colony is spread out along some six miles of beach front- the North Colony is the largest, with about 40,000 breeding pairs (direct counts are made from aerial photos early in the season- one black dot equals one nest). Middle Colony has about 2000 breeding pairs, and South Colony around 13,000. North Colony is not only largest, but the most spectacular, bounded on the north with the dramatic ice front of the Bird Ice Cap, and Beaufort Island off in the distance. During our time at the hut a huge, tabular iceberg drifted into view and added to the scenery. Kerry pointed out some observations about the state of the colony this year, some of which we had already observed at Royds. The birds are behind schedule (not as much as Royds), and the huge variations in maturity are evident- tiny nestlings right next to chicks that have almost molted into adult plumage. Stream flow off the melting glacier is providing some problems for the birds as well, as nests are being flooded and chicks are stranded on tiny islands in the midst of a glacial stream. I also observed a waterfall draining off the ice front of the glacier into the sound, a sight I have not seen before. It is too soon to implicate global warming in the recent melting, as the alluvial channels already exist and were obviously created by stream flow in the past. But the mismatched timing of the birds' reproductive cycles, the continued presence of non-breeding birds in the colony (they are usually gone by now, and only breeding parents still around), and the significant melt and stream flow off the glacier all suggest that something is awry in the Ross Sea ecosystem.

Panorama view of the Cape Bird North Colony (NZTV news crew in left center).

Flooded nest sites in the North Bird Colony (left) and a waterfall off the Bird Glacier front (right).

Grounded ice provides a handy spot for shoreline activities.

More penguin activities on ice along the beach at Bird.

Even penguins can slip on ice!

Skua pair give the territorial warning to other skuas flying over.

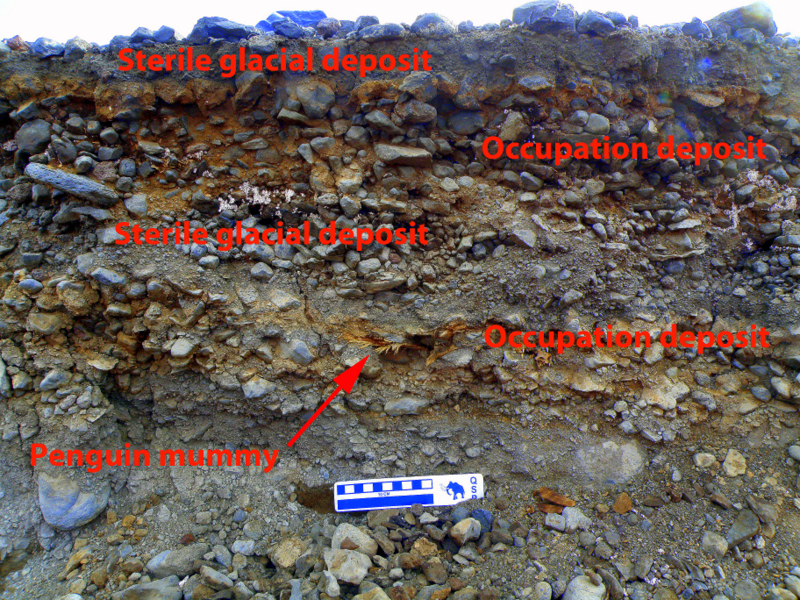

The last time we were at Cape Bird, we excavated several sites in the North and Middle Colonies, but the weight of the sediment bags severely limited how far abroad we surveyed (our methods then were to screenwash all the sediments from a 1 X 1 m test pit that often went down to 15-20 cm in depth). We felt that we had a good idea about the distribution of sites then, but we found this time that our search pattern is much more refined now. Between Middle and South Colonies we found evidence of almost continuous occupation, implying that the overall Bird colony was much larger in the past. Pebble accumulations were on most prominent terraces and along raised beaches, and everywhere we probed the tell-tale red color of ornithogenic soil confirmed our assessment. Most interestingly, we found several exposures along the sides of meltwater drainages that bisected abandoned sites, allowing us to use alluvial stratigraphy to investigate the former occupations. One site, south of Middle Colony by .75 km was most revealing: a cap of sterile, glacial sediment covered a significantly thick layer of ornithogenic soil. Below this occupation layer was another sterile glacial layer, but below this was a deposit from an earlier occupation, and a penguin mummy was eroding from the top of this layer. We immediately began to suspect that we were finding evidence of earlier occupations of Cape Bird, perhaps during the Penguin Optimum (2000-4000 years ago).

Bright red ornithogenic soil (left) and a site in an abandoned colony on McDonald Beach, Cape Bird (right).

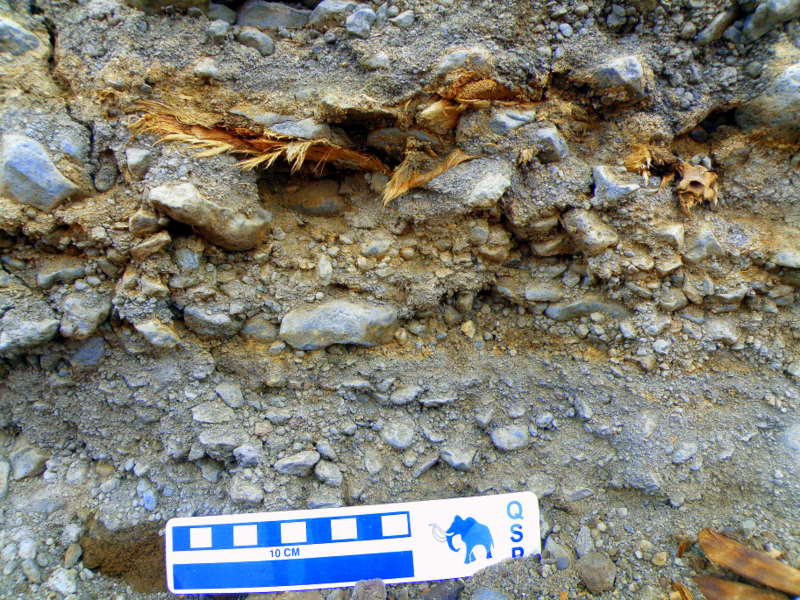

Details of the alluvial profile showing two distinct periods of occupation (left) and close-up of the penguin mummy in the profile (right).

Over the next three days, we covered over thirty miles of walking while surveying for additional sites and calculating the area of the former occupations (I record tracks continuously with my GPS to keep track of where our surveys went). Another alluvial profile well south of the South Colony caught our attention. An alluvial exposure of more than 3 m was exposed on the south side, and around 2 meters below the surface Steve spotted a feather imbedded in the deposit. With some more examination we found several more feathers, including a tail feather quill that is plenty large enough to be radiocarbon dated. We hypothesized about how long it would take to accumulate such a significant amount of material above the feathers, and concluded that in this very dynamic landscape it could be 10s of 1000s of years, or perhaps only one or two cataclysmic episodes. The results of the radiocarbon analyses will be revealing.

3-meter-high alluvial exposure south of South Colony, below Shell Glacier (left) and a feather from around 2 m depth (right).

As always on our walks around the raised beaches we found a lot of interesting seal remains, from almost complete mummies of unknown age, to more interesting skeletal elements. And of course we frequently encounter live Weddell seals as well, since they love to haul out onto the beaches for sunbathing. Cape Bird is also a favorite of mine for the constant parade of beautiful icebergs drifting past- some that look like ice sculptures, others like medieval castles. And the penguin activity along the sea is always entertaining, as the birds march up and down the beach, and frolic among the brash ice washing around the shore.

Weddell seal mummy along Cape Bird beach terraces (left) and details of a seal femur (right).

Details of the extreme adaptation of foot and toe bones in the seal flipper (left) and a Weddell seal relaxing on the beach (right).

Weddell seal hauls out on the beach at Bird- it looks strenuous!

Artistic icebergs along the beach at Cape Bird.

Views of Adélies along the ocean front at Cape Bird.

Beach encounters at Cape Bird.

Penguin posse takes over the beach.

A skua makes a dual attack- Steve first, then me.

Our time at Cape Bird ended too soon, but before our departure a team from New Zealand TV arrived to shoot footage for a report on work by New Zealanders in Antarctica. Kerry and her young assistant Isaac obliged the filmmakers with interviews and excellent views of the activities on the colony, but before they were through we heard the rotors of our helo coming over the glacier. We headed for the beach and watched the helo tech solve the jigsaw-puzzle problem of fitting all our field gear and us into the 212. The take-off and hop down the beach to pick up the last of our sediments was a bit tense, as the pilot verbalized his discomfort with the maneuvers involved, but soon we were powering up over the glacier and onto the slopes of Erebus for the ride back to McMurdo. The sky was clear, and the views of Erebus and McMurdo Sound were spectacular. Now we are washing and processing sediments to get ready for another foray into the field. Plans at the moment include a trip to some southern capes and islands that we’ve heard rumors about having evidence of ancient colonies. The trip to Beaufort Island is currently scheduled for January 27th, but it sounds like that may change. I’ll write another update again soon.

View of west side of Mt. Erebus from the helo (left) and ship channel created by the icebreaker Oden, at top (right).

Cheers! Larry