Update #8: Two Trips to Cape Crozier

We did finally make the trip over to Cape Crozier to round out the triumvirate of Ross Island Adélie colonies, but our work there was a bit anticlimactic, as I’ll explain in a moment. We loaded up in 36 Juliet one more time, and traversed around the south side of Ross Island this time, crossing over the southeast flank of Mount Terror before turning north towards Cape Crozier. The conversation between the helitech Ally and our pilot Marco was a little disconcerting, as they were having trouble with the GPS (“the button sticks sometimes”), and Marco was unfamiliar with the route. I considered passing up my Garmin, as I have the high-resolution map of Ross Island installed, and was tracking our flight in progress. But he seemed to work out the problem, and soon we were wrapping around Tarakaka Peak to swing into the Cape Crozier hut helipad, just outside the boundary of the ASPA. Conditions in McMurdo when we left were clear and fairly calm, but things change rapidly as you near Crozier, and as we turned north the ship bucked wildly as Marco mentioned were encountering 40 knot winds. Clouds swirled around the summit of Terror and several other sub-peaks, but visibility was unlimited below the ceiling, and as we flared for landing the winds completely died, much to Marco’s surprise.

Short clip of the helo ride around the southeast side of Mt. Terror.

Flying into Cape Crozier under the cloud ceiling (left), and the 212 readies for takeoff at the Crozier hut pad (right).

Some folks from the BFC (Berg Field Center) were already at the hut, having stayed over the night before to break down equipment for the winter closure, and they began loading the ship with gear as we exited. One decided to frantically wave us away from the helo, as though we were about to be chopped to bits by the rotor, although the pilot and Ally were fine with where we dropped our packs to gear up- it’s another McMurdo thing- some folks still think all “beakers” are too clueless to perform field procedures safely, and must be told what to do. It’s a bit annoying when we have numerous field seasons and many helo hours behind us, but it’s still a part of the culture here. We were already hiking before the ship lifted, and since we knew that Marco would lift and pivot to take off downhill, our flight gear was untouched by rotor blast. We hiked to the top of the ridge beside the hut to get our bearings, and started down towards the colony.

Liu at the helipad below the Cape Crozier hut (left), and hiking to the ridge above the colony (right).

Our objective was to examine a series of exposures in the colony that were reported to contain evidence of multiple occupations. Grant Ballard, one of the long-time Crozier bird biologists had found the sites during his many seasons here, and had given us waypoints for 4 localities. We traversed from the ridge into the center of the main colony and headed for the first waypoint. The birds were pretty far along in their breeding season now, and the chicks were all in crèches and no longer under constant guard by parents. I was again struck by the variable maturity of the chicks- some were almost completely molted with only remnants of gray chick down showing, but many others had no adult plumage showing at all. And an occasional chick was half the size of its peers, and stood zero chance of fledging before winter arrives in only a couple of weeks. We arrived at a set of nests along a ridgeline with the sides dissected by erosion, and I confirmed we were at Grant’s site 1. It was quickly apparent that Grant had been fooled by the stratigraphy- it initially fooled me too, although Steve saw the problem right away. The current occupation layer was only a few centimeters thick, and was underlain by sterile volcanic material. Perhaps 35 cm below that was what appeared to be another ornithogenic layer, with chick mummies, feathers, and bones imbedded in it. But as Steve immediately surmised, it was just a terrace in the volcanic sediments that the penguins were utilizing now. When you traced the layers back into the profile the occupation layer vanished, and only a meter or so of cinders and gravels were exposed. Our previous work here had concluded that the Crozier colony was quite young (500 yr BP), and we were looking forward to some new data that might modify our hypothesis, but now that appeared unlikely. Steve sampled a few feathers from the bottom of the active layer just to make sure, and we headed south towards the remaining waypointed sites. At each exposure we examined the pattern held- a shallow active deposit from the modern birds, then sterile sediments beneath. No surprises were in store for the occupation history of Cape Crozier.

Grant's Site 1 at Cape Crozier (left), and the exposure with the false occupation layer at Steve's knees (right).

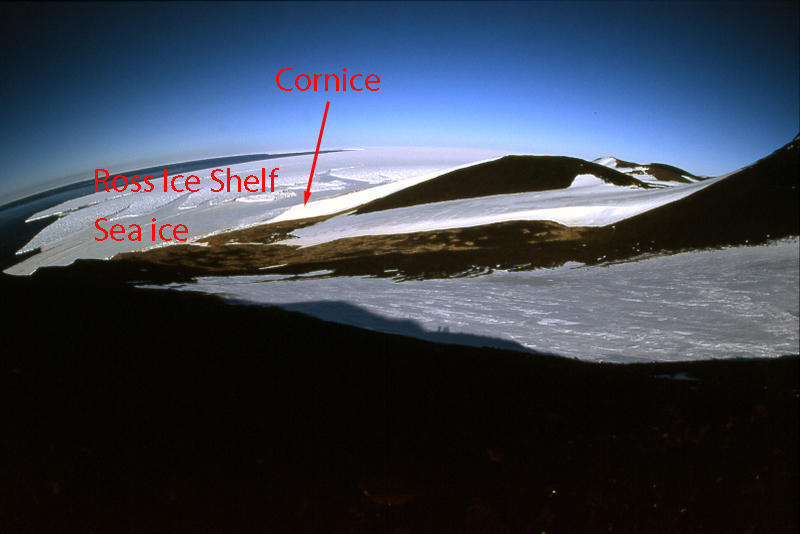

As we worked our way through the colony to check out the exposures, I was captivated again by the complicated geography of Ross Island’s largest colony, and the fifth largest Adélie colony in the Ross Sea. When we were here in 2001, the colony size was estimated at 250,000 breeding pairs. Now new remote sensing techniques (aerial photography early-season when all breeders are on nests) with direct counts of birds in the photos has pared that number down to around 180,000. Many birds have situated their nests within a short distance of the shoreline, so they don't waste a lot of energy in transit. But whole portions of the colony are far up the hillside- one noteworthy portion is accessed by a central gully system and the highest sites are more than .75 km from the sea. The penguins use this gully as a “penguin superhighway” to march up and down from nest to seashore, undoubtedly burning much of the precious food in their stomachs and thus limiting their ability to support the growing chicks. Another whole sub-colony is located to the southeast of the main colony, separated cleanly by a permanent snow feature called the cornice (actually a permanent snowfield that is steepened by a wind-blown, corniced top). In years when the sea ice persists along the shore, the birds in the “East Colony” would have to travel kilometers to the ice edge, again reducing the chances of breeding success for its residents. It is clear to me that colony demographics would be revealing about which birds stand the greatest chance of passing their genes on to the next generation, and although I know the penguin biologists are trying to investigate such patterns, studying such a large colony in this detail would be next to impossible.

The main colony at Cape Crozier high on the hill (left) and the "penguin superhighway" used by the birds to reach the high sites (right).

A shaky video clip of rush hour traffic on the "penguin superhighway" at Cape Crozier.

One other observation interested and alarmed me as looked over the colony and its setting- in the ten years since we were here last the ice conditions have changed significantly. I clearly remembered a fast-ice shelf along the entire beach front that the birds traversed to reach the water, and a large expanse of sea ice covering the inlet between the Ross Ice Shelf and the colony. And the shelf itself projected further out into the Ross Sea ten years ago, but without comparison to my previous photos I couldn’t be sure how far. Once I got back to my computer and could bring up photos for comparison I could see that the front edge of the Ross Ice Shelf had retreated by close to a kilometer. The sea ice conditions vary from season to season, but the gradual calving away of the front of the shelf is worrying. Several of the large tabular bergs that have made the news lately as they drifted around the Ross Sea and beyond have separated from a portion of the ice shelf just east of here, but the difference between hearing about it on the news and seeing it with your own eyes was a bit stunning. It is also clear how this portion of the shelf acts as a gateway for Adélie occupation here- when the shelf extends farther out, access to the beaches at Cape Crozier for penguin occupation is blocked. As the shelf retracts, the site becomes ideal for Adélie occupation, with snow-free volcanic slopes for nest sites, nearby rich feeding grounds from the seasonal melt of sea ice, and short access to the sea along the shelf edge. The short occupation history of Cape Crozier may provide a minimum age for the retreat of the shelf to the proximity of this corner of Ross Island- prior to that the colony site was too far from the ice edge for the birds to roost here.

View of the ice situation in front of the colony in 2001 (left) and 2010 (right): note location of the Cornice feature for reference.

Since we so quickly concluded that we wouldn’t be finding evidence of previous occupations of the main colony, Steve and I decided to hike to the top of the ridge above the cornice to take a look at the East colony. The loose volcanic scree of the slope was tedious, but the hike geologically interesting as mixed in with the jet-black and red volcanics that composed the slope were a variety of granites, schists, and other exotic rocks transported here by glaciers. The view from the top of the ridge was a great vantage point for the span of the entire colony, and we could see far up the flat, featureless expanse of the Ross Ice Shelf. Liu joined us and wanted to investigate the Skua Lake (another overused title- almost every point has a “Skua Lake”), so we plunged down the scree to the east. The territoriality of skuas vanish when bathwater is available- large numbers congregate in these ponds for bathing and drinking. The skua chicks are also getting pretty mature at this late date, and I found that the parents are only half-heartedly defensive as you hike near the almost adult-sized chicks (rather than the full-on attack you receive when they are younger!). As we had surmised from above, the sediments in the lake were composed of gravels, and were not penguin affected, so Liu did not want to sample here. Steve and I debated descending to the East colony, but we’re sure it is no older than the main one. The long trudge back up the ridge occupied the next hour. Once on top again, Liu unfurled a custom-made flag created to commemorate this expedition to McMurdo and the Ross Sea, so we shot some photos for him to take back home.

Steve high on the ridge above the Cornice feature, between the main and east colonies (left), and Steve and Liu at Skua Lake (right).

Skuas enjoying Antarctic life in Skua Lake.

Mature skua chick that is molting into adult plumage (left), and Liu's commemorative flag for our expedition (right).

We returned to the main colony to reassemble our crew for departure. One more visit to the beach was rewarded with more views of penguin character and antics. I always enjoy the activity in the surf at the bottom of colonies- the birds virtually body surf in from the sea, and witnessing their prowess in the water is amazing. Adélies are also very comfortable on ice, even steep ice, and the sheer edge of the Cornice and its attached snowfield are speckled with penguins on every available nook and cranny. As our pickup time neared, we started back towards the hut and helipad. The Crozier hut was not sealed up for winter yet, so we went inside while we waited for the 212. I have fond memories of the hut from when we spent a week here in 2001, and not much has changed since, save the addition of a wind turbine generator powering the radio and running a new Wi-Fi router. Interesting documentation and art decorates the hut, commemorating when it was built and many long field seasons here by penguin biologists since. My anxiety over the weather preventing our pickup was pointless, as conditions never worsened and visibility was unrestricted for the approach of the helo. The ride back around Mount Bird and across the shelf was as gorgeous as always- one flight alone yields views that would allow you to describe most aspects of periglacial processes and glacial dynamics from the varying polygons, glaciers, seracs, tongues, and crevasse fields you pass above. We were back on the pad in McMurdo by 17:50, so in plenty of time for dinner at the galley!

An Adélie bodysurfs in to shore (left), and sleeping penguins adorn the ice cliff of the Cornice (right).

The interior of the small-but-efficient Cape Crozier hut (left), and hut artwork by past penguin biologists (right).

Amazing crevasses on the flanks of Mt Terror (left), and classic polygons on unglaciated slopes nearby (right).

In discussions over dinner, Jurek expressed an interest in going back to Crozier as he found more plant life there than he expected. Liu likewise wanted to return, but this time without his heavy field pack and instead focusing on photography. Steve and I weren’t terribly interested in pushing our luck with the fickle weather again, but Steve reluctantly agreed to go again with them. I felt a bit guilty about bailing, but when we talked to Julie at Helo Ops we found that we made her day by reducing the size of our party- three carpenters needed to go to Crozier to close up the hut for winter, and with only three of us going that could be done in one trip. Next morning I settled at my computer to work on my web class as Steve, Jurek, and Lui headed for the helipad. I had responded to only a few discussion postings when the boys walked back into the lab. Crozier was socked in, and the pilot had told them he could maybe put them down, but it was very unlikely he could get back in later to pick them up. Cool heads prevailed, and the flight returned to McMurdo. Steve had noted that one additional seat had been available, so he wisely added me to the manifest for another attempt the next day. As he predicted, my guilt got the best of me, and I was along for the second try on Wednesday. But conditions then looked even less likely- other pilots were calling in with unfavorable reports about what they could see out east, and a large cloud bank obscured much of the south side of Mount Bird. The carpenters’ job was important, so our pilot decided to go as far as he could to decide whether to scrub the mission. As we neared the cape, a window through the clouds was open, and this time the passengers agreed to be dropped off, even though getting stuck was a distinct possibility. I figured we could always get the carpenters to re-open the hut if things got bad, so we dropped to the pad and unloaded.

Low clouds hang around the summit and slopes of Mt. Terror (left), and another fabulous crevasse field on the slopes (right).

Steve did have some more work for us- in a side study he is comparing isotopic signals from birds at various colonies, various times (past and present), and in various conditions (thriving, starving, etc.). Scott and Annie, the two penguin biologists that spent the season here, had collected feathers from live chicks during wellness checks. Now we were going to collect feathers and toenails from chicks that had not survived this breeding season. Chick carcasses were evaluated on condition of the birds at death (determined by visible fat layers), cause of death (obvious skua kills or possibly starvation), age at death, and whether or not the carcass was scavenged by skuas. We moved around the colony looking for recent carcasses in a stiff, cold wind, with Steve doing the gross stuff and me recording data. Carcasses from many seasons are present all around the colony, and in some places are stacked up like the aftermath of some past penguin Armageddon. As we moved about the colony it was clear that the pattern of mixed maturity of chicks was prevalent here as well- some tiny, downy chicks are still around, while right next to them are almost-molted juveniles. I couldn’t get a clear sense of the ratio, but it seemed to me that almost a third of the birds were behind schedule.

Steve samples feathers and toenails from a chick carcass for isotopic analysis (left), and the mixed maturity of chicks in creches at Cape Crozier (right).

Piles of old penguin carcasses at Cape Crozier (left), and details of one carcass of unknown age (right).

The Peter Frampton look on an almost-mature chick (left), and Adélie heaven on icebergs just offshore (right).

After a couple of hours we collected 30 samples, which was plenty to get Steve’s students started on their pilot study, so we began trudging back up the hillside towards the hut. The carpenters had checked in with us earlier, having finished their job, and told us that a helo might come earlier than scheduled. Visibility was no worse than when we flew in, and as the hour grew later it improved further. We hiked around a bit, then made our way back to the hut to await our ride. As the sun dropped to its evening position in the west, it warmed the volcanic rocks around the hut and created quite a pleasant temporary climate. We heard from Helo Ops that the 212s were both very busy, so we couldn’t expect an early pick-up. As our scheduled time arrived, the word came in that an A-star (the smaller helicopter) would be sent to pick us up in two trips (A-stars can only hold four passengers at a time). Marco flew in and landed in light winds, and we got the first ride out. I had forgotten how much fun it is to ride in the smaller helos- I got the front seat next to the pilot (the 212s have controls in both front seats, so only helitechs can ever ride ‘shotgun’). The views of the periglacial ground, the glaciers and crevasses, and Mt. Erebus were spectacular. A thin, wispy cloud wrapped around Erebus, and a small plume of gas and ash dribbled from the active cone. We got a great view of New Zealand’s Scott Base as we flew over, and the literally thousands of Weddell seals that haul out from the ice cracks at the pressure ridge just off shore from the base. We flew past the new wind turbines that now power Scott Base, and set down at the helipad. As we lugged our field packs back to the lab, it hit us that our last field trip of this field season was now behind us. Now our efforts would be directed again to logistics- checking back in all our field equipment to the BFC, and our radios back to Comms, readying boxes of samples for cargo, cleaning the lab, and finally packing and “bag dragging” for our flight off the continent. I’ll write one more update with some concluding thoughts about this field season.

Launching from Cape Crozier in the front seat of the A-star.

View of Mt. Erebus from the A-star (left), and Scott Base (right)- note that all the dark spots on the ice are Weddell seals!

Cheers! Larry