Boredom, excitement, and an auspicious anniversary

It's amazing how fast things can go from utter boredom down here to high excitement. The boredom occurred because after our outing to Cape Royds we suffered FIVE cancellations of scheduled helo flights into the field: one rather obvious due to a blizzard, but the other four on otherwise pleasant days but with the helo pad or the destinations socked in with low-hanging fogbanks. Helicopter work down here (and most everywhere else) is strictly visual, so when fog sets in the ships don't fly. Day after day we woke to foggy conditions that mostly persisted the whole day, or certainly late enough that we couldn't go out for a day trip. Helo operations were backed up significantly, with only a few short work trips accomplished, so there was much catch-up to do once the weather improved. Finally, on Friday, we woke to clear skies, light winds, and we were scheduled to fly at 10:50 AM.

Click on the images below for a larger version.

A blizzard shuts down helo flights, as did the fog enveloping Ob Hill.

But before our departure time arrived a bit of commotion unfolded on the helo pad (we can look onto the pad from our lab window)- I noted the arrival of an ambulance and a number or firefighters in full gear awaiting the arrival of a big Bell helo. My first thought was that there had been an accident in a field camp, and a number of possibilities sprang to mind: burns from campstoves, CO poisoning from poor ventilation, trauma from someone taking a tumble in the field, etc. The ship arrived, someone was loaded into the ambulance, and a series of runs between the medical center and the helo pad ensued- I counted at least three trips. With our curiosity (nosiness) overwhelmed, Steve left to ask the Crary folks what was up, and word came back that the worst-injured of the sailors from the Korean fishing vessel that had caught fire up north in the Ross Sea had been evacuated to McMurdo to be flown back to Christchurch for treatment. It had turned into quite a rescue- the US icebreaker Palmer had been headed to McMurdo and met up with the ship and its sister on the way south, transferring the most seriously injured aboard. Transfer to helos was only possible when the Palmer cut a U-shaped channel into the sea ice so the helicopters could land alongside and transfer the victims aboard. Then helos brought them here, they were checked out at medical, then moved immediately out to Pegasus and loaded aboard a waiting C-17. Five and a half hours later they were arriving in Christchurch for treatment. Once again we were witness to awesome capability of the American program to execute incredible rescues, but also the complicated and expensive logistics involved in succeeding in such efforts. And of course, if the weather had been uncooperative at the time none of this would have been possible. Now if we can just find out why a pair of Korean fishing vessels were operating in the closed marine sanctuary of the Ross Sea….

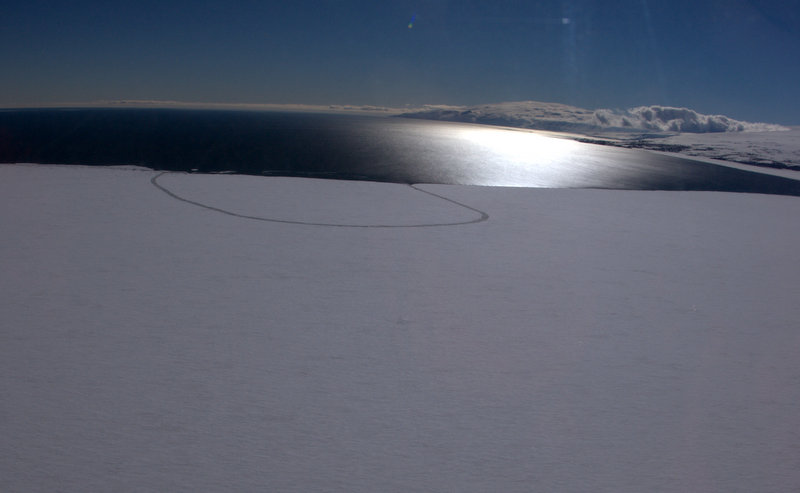

An ambulance meets the 212 on the helopad, and the U-shaped channel cut into the ice edge.

With the early morning's furious activity behind us, we geared up and headed to Helo Ops for our flight. The Helitech ran us through the usual safety procedures, which is important but always reminds me of the advice on water landings in commercial airlines- the chances of you getting the chance to use that life vest in the water is pretty remote. In the same way the chances of you needing to shut down the helicopter after a crash that left the pilot and Helitech incapacitated seems like an unlikely (and grim) possibility. We handed up our gear to Nora, the Helitech, and got packed into the back of one of the 212s for our flight. Since I track all our trips with my GPS, I was surprised to find that the flight out to Cape Geology in Granite Harbor was over 90 miles- everything seems much closer than it actually is, and the ships are flying higher and faster than it seems (averaging 138 mph for a 50 minute flight). Some discussion ensued about the landing site at Cape Geology- the ASPA (Antarctic Specially Protected Area) document specified a small helo pad on the beach, that I thought I could see on Google Earth. But when we arrived it turned out the square in the imagery was a tent platform, and the landing pad was much more obscure. Our pilot Jack Hawkins had gotten some advice from Rob, and spotted the tiny, somewhat level spot alongside a large boulder with cairns on top. I had suspected that Jack had probably learned how to fly this aircraft in the jungles of Viet Nam, and his finesse at maneuvering this big beast onto that tiny pad supported that hypothesis. I would liken it to parallel parking a Hummer into a tight slot, but with rotors furiously spinning above you only inches from the rocks ahead. Jack had to ease in, start to weight the skids, then based on how the ship was settling lift again, back up for another look, then slip forward and down again. Once we landed and disembarked I noted that the landing site was only the length of the skids, no room for margin at all. All in a day's work for Antarctic helo pilots.

Video: Jack squeezes into the tight helopad at Cape Geology

Jack was picking up a Kiwi crew that had been working at the ASPA for the past few days, doing some detailed boundary mapping, etc., and they of course had spent an extra couple of days out due to the foggy conditions, but they had no complaints about being stranded in such a pleasant spot. Nora loaded their gear, they boarded, and after we confirmed comms with the ship, Jack departed for McMurdo. We surveyed our new surroundings as the sound of the copter faded away in the distance. Cape Geology is a rocky headland next to a shallow bay (Botany Bay), and is composed of granite cliffs and boulders bisected occasionally by jet-black dikes. My first interest was in locating the Granite House- a small rock shelter constructed by a geologic field party from Scott's Terra Nova expedition when they spent six weeks here studying and mapping the local terrain. A short hike down the boulder-strewn beach led right to it- all that remains are the constructed walls, a few metal containers, and a part of seal skin that once served as a roof. The party, led by Australian geologist Griffith Taylor, had constructed Granite House as a field kitchen, to keep the fumes from seal blubber stoves out of the sleeping tent. They used a small defile between three boulders as the foundation, then constructed three-foot-high rock walls to enclose the space. Historic photos from the expedition show the cracks between the granite blocks tightly chinked with moss, a secure roof formed from an inverted sledge covered with seal skins, and the chimney from the blubber stove extended several feet above. Today not much remains of the historic structure- as recently as 1959 numerous artifacts were still there, including a sledge, an ice axe, several boots, and two books in perfect condition (books by Jules Verne and Edgar Allan Poe), but over the years these have disappeared, and in a 1981 visit none of these were found. The site was officially documented in 1992 (Schroeter et al., 1993), and a final artifact was found- rusty cigarette tin containing a note to the skipper of the Terra Nova revealing their travel plans (as with so many field parties during the Heroic Age, the ship was unable to reach them because of ice conditions, so they were forced to make their own way back to Cape Evans!). To us, the noteworthy part of their message was the date they left for their trek- January 14th, 1912. We were looking over Granite House on January 13th, 2012- 100 years to the day from the last full day the field party spent here before departing for points south.

The boulder-strewn beach near Granite House, and several views of the Granite House exterior, interior, and the few remaining artifacts such as the seal skin that was a portion of the roof covering and a fuel can.

After we finished taking photos of Granite House we headed around the corner of the cape to check out Botany Bay. It was immediately clear that fossil Adélie sites were unlikely, there were far too many boulders and no adequate beach, but we wanted to check out the site anyway. The ASPA protects a unique and profuse botanical assemblage- Jurek told us that 29 lichen and moss species had been identified (Seppelt et al., 2010), ranking its biodiversity as the highest in continental Antarctica. Since our survey time was limited, Jurek dove right into his collecting efforts, moving as fast as good methods would allow. Steve and I hiked across the bay to the one small beach that potentially could yield penguin remains, enjoying some of the most pleasant conditions we have encountered- no winds and strong sunlight focused directly on the north-facing boulders and cliffs provided temperatures so mild I wore only my base layer and Steve stripped down to a t-shirt! Not only is Botany Bay gorgeous, but it is extremely unique in its physical environment. Snowmelt-fed streams cascade over the rocks, feeding broad wetlands covered in plant life. Unlike most regions of the Scott Coast defined by black and white rocks and glaciers, color was abundant. Granite boulders ranged from cocoa-brown to rose-to-rust-red, and between lay verdant wetlands carpeted in green bryophytes, red and orange lichens, and dark intrusive rocks. And of course surrounding the cape and bay was the typically spectacular Antarctic landscape- in this case the glaciers and cliffs of Granite Harbour. As we walked we were under constant attack from the large skua population that also merits ASPA protection- 40 to 50 nesting pairs have been documented and Steve came up with a count of at least 28 pairs on our short walk. I have been trying to capture good video (and audio) of the skua long call, most prominent when one of the mates returns to join the other, but the timing is tricky and I haven't really gotten what I want yet. After only a scant few hours in this amazing place we rejoined back at the helopad just before Jack radioed to tell us he was minutes away. Jurek came sprinting across the boulders at the last minute after stretching his collection efforts to the maximum, and we handed our bags up to Nora, re-boarded the 212, and headed back to McMurdo in time for dinner.

Video: Steve surveys the high bench above spectacular Granite Harbour

Video: A snowmelt-fed stream and wetlands at Cape Geology

Video: Antarctica skua long call

Dark, intrusive rocks surrounded by white granite at Cape Geology. Diverse botanical assemblage of mosses and lichens in Botany Bay, including the endemic lichen species Umbilicaria aprina (center right). Jurek dwarfed by icefalls and mountains just left of center, bottom left image, and more views of spectacular glacial scenery in surrounding New Harbour.

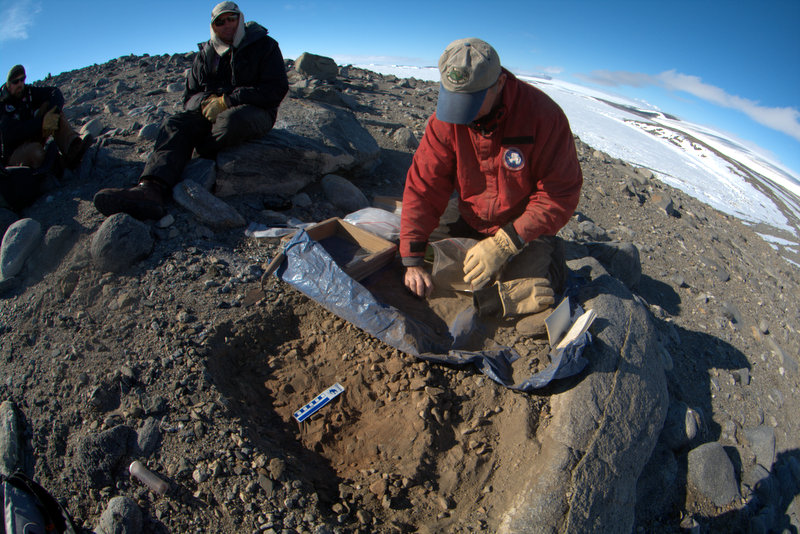

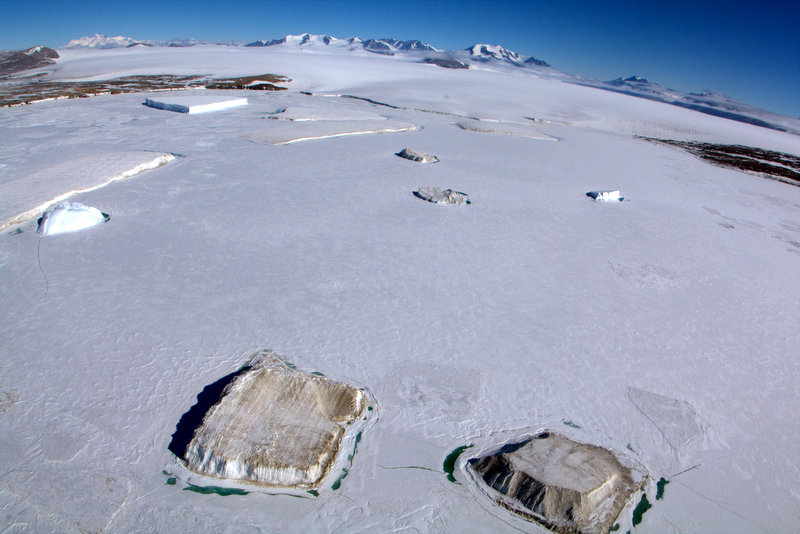

Arriving back in McMurdo we found that our flight for the next day had been scheduled for an 8:30 AM departure, meaning an early day (passengers must be on the pad 45 minutes before flight- more McMurdo rules). Our plan was to visit Dunlop Island and Spike Cape, both to relocate and confirm the coordinates of our 2001 sites, and to survey for new ones we may have missed before. We also had a helicopter on close support, meaning that the helo stays with us for the day and moves us around as needed. It’s a great situation for us because of the convenience of having the helo at the ready for movement as needed. But it can be a mixed bag for the pilots, some just hang around the ship and wait for the chance to get airborne. Fortunately our pilot today, Paul Murphy, was very much into hiking around and was interested in our work, so I think he and Helitech Geoff Miller had a good day. I told him how envious I was of their lives flying high above Antarctica getting the big-picture view of the landscape. But Paul said that often he wants to get down on the ground and see things up close. The sites we were bound for are further south than New Harbour, so the flight over was a bit more than half an hour. The visibility was unrestricted, but a banner of clouds hung just over the flight altitude of the 212, so the light across the sea ice and frozen-in icebergs was soft and magnificent. We set down on Spike Cape proper to start our day, and I circumnavigated the headland while Steve looked around on the landward side. I didn't find a thing, but did spot a pair of Emperor penguins far out on the ice. When I returned to the helo I found Steve happily excavating a shallow site only 30 meters away. The pebble mounds covering them were subtle, and it was easy to see how we missed them before, but the preservation was excellent and we recovered bone and feathers from two small test pits. We found we couldn't reach the long beach line as a narrow strip of sea ice blocked the way, so Paul and Geoff loaded us up for a short hop to the beach. They then departed for Marble Point to pick up some fuel, and left us on our own for a while. We thought we remembered old mounds emerging from below the Wilson Piedmont Glacier on this beach, so we walked to the north end to check it out. Our memories must have been faulty, as this wasn't the place, so Steve and I set out to see how much of the beach we could survey before the helo returned. Once again distances were much greater than they appeared, and we were unable to get to the farthest southern end, although I'm sure we walked a good five miles each way. The sediments on all the terraces had been greatly disturbed by successive advances and recessions of the glaciers edge, and all the freeze-thaw action in the periglacial sediments, so even though I suspect the birds had colonized here in the past, there was no evidence left today. As we returned to the survival bags for pickup I spotted a seal mummy on the second or third raised beach terrace- it was very well preserved and turned out to be another crabeater seal- the second we've found along this southern coastline. After a short wait were heard the 212 off in the distance, and soon we were on our way back to the base once again. The flight back was uneventful, and I noticed Steve, Tao and Jurek briefly nodding off. I was entertained photographing the amazing variety of frozen-in icebergs around McMurdo Sound. The addition of two new sites to our database made the day's efforts very worthwhile, and although we had not made it to Dunlop Island this time, we can reschedule that for after we return from Cape Bird. Now the Monday helo schedule is out, and we should be flying to Bird mid-morning on Monday. I'll write another update when we return.

Video: Steve surveys the LONG beachline at Cape Spike along the edge of the Wilson Piedmont Glacier

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Soft light on the Sound, sea ice, and icebergs on the flight to Spike Cape. Steve excavates shallow sites at Spike Cape- pilot Paul Murphy and Helitech Geoff Miller look on. Steve at the glacial front of the Wilson Piedmont Glacier. A partly mummified crabeater seal on the beach at Cape Spike. A variety of frozen-in icebergs along the Marble Point coastline.