Camping at Cape Crozier

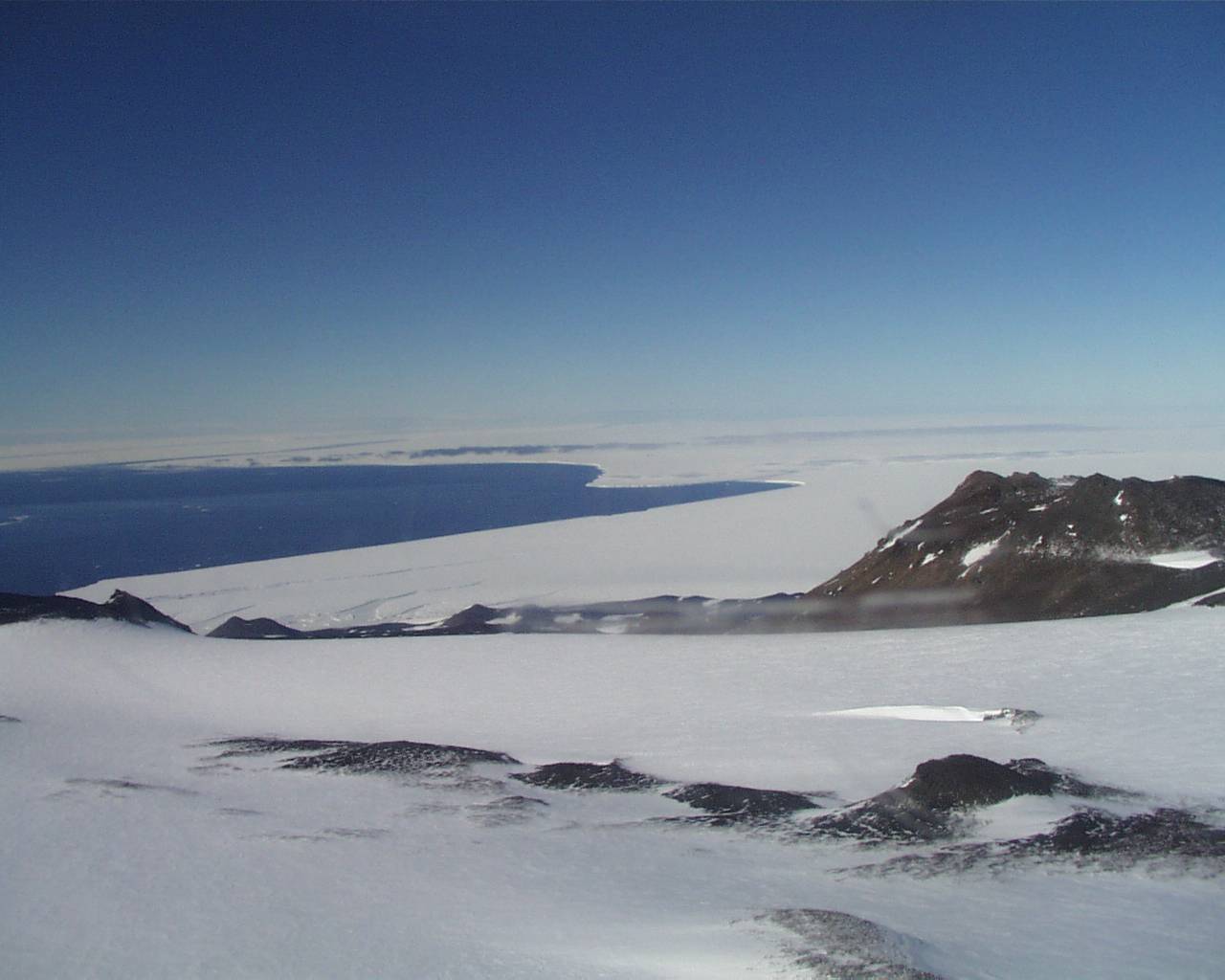

The technique of flying helicopters to field camps, or dealing with “helo ops” as they term it down here, is getting routine but not lacking in excitement. The flight over the saddle between Mount Erebus and Mount Terror was spectacular, flying over glaciers hundreds of meters thick riddled with huge crevasse fields. The NSF policy forbids flying over the open ocean in case of mechanical malfunction of the helicopter and the need for an emergency landing, but I dread the result of a hard landing in such terrain. It might be better to expire quickly in the frigid water rather than to die more slowly in this icy landscape. But no worries on this flight, a quick 30 minutes out of McMurdo we were circling for a landing near the Crozier Hut. This hut is maintained near the Crozier Adélie colony for the benefit of researchers who spend the season out here studying these birds. Similar facilities are set up near several other large colonies. Steve had already learned that a former student was one of the researchers, and we were offered a warm welcome by radio before arriving. Once we unloaded the ship and checked in with McMurdo, we decided to walk down to check out the colony. A protected airspace is enforced over the colony, so the heli pad and hut are purposely located out of sight and sound of the birds. As we approached the crest of the hill in front of us, a steady pulse of sound became audible, and cresting the hill the colony spread out below us. Point Crozier is located on the transition between the backside of the Ross Ice Shelf and the open sea, so the view spread out below us was breathtaking. Flat shelf ice abruptly ends near the end of the point, and icebergs calved from the shelf drift out into the current and often become grounded in the shallow tidal areas around the point. And covering the hillside is the colony, consisting of at least 125,000 nested pairs, most of which have two chicks, as well as a huge number of non-breeding birds present this year. The sheer number of birds is staggering, the sound, sight, and odor overwhelming. The hillsides are alive with birds, rapidly ascending or descending the slopes to the ice shelf, traversing the ice to sea, and diving into the water in waves of dozens(?) at a time, as other waves fly out of the water to land standing on the shelf ice. The water is cleaved with penguins in large groups, porpoising along the surface to find their way, and then diving deep for krill. The colony is in constant motion, with chicks vying for a regurgitated meal from a parent, non-breeders playing “house” to learn skills for breeding, and parents rapidly traversing from nest to sea and back, maintaining a steady flow of calories for rapidly developing chicks. I have never seen such an amazing display of life in one place.

Deep in the colony we found one of our hut-hosts, Michelle Hester, Steve’s ex-student who went on to create a career for herself in natural science. Michelle welcomed us to Point Crozier, and offered to cook dinner for us as well, so we spent more time with the birds and forgot our new radio check-in time at 8:00 pm, but fortunately her partner, Grant Ballard, anticipated our delighted shock at arriving at the colony, and checked us along with their call. Eventually we arrived back at the hut, moved into our tents (already pitched and waiting), and retired to the hut for dinner and drinks with our gracious hosts.

Part of Steve’s research plan is to study modern penguin deposits to compare to fossil ones, and to produce taphonomic data concerning fossils and diet remains, thus one goal at Crozier is to excavate a test pit in a modern penguin colony. We had been warned that this work was going to be messy, but unlike colonies that Steve has studied on the peninsula, it never rains here, so the sediment appeared dry and we anticipated an easy time of it. However, the dryness was only skin deep- as soon as deeper layers were penetrated a goo of ornithogenic soil and penguin urine oozed into the test pit. And it doesn’t smell very pleasant, either. Dry screening was out of the question, we couldn’t reach the ocean because of ice remnants along the shore, so wet screening in the field wasn’t possible either. Now the no-fly zone over the colony created a problem for us, as usually we can leave heavy sediment bags where we excavate and have the ship pick them up at the site. This time we were forced to lug them one bag at a time (25 kg each or so) across the colony to a nearby snowfield, and load them into a banana sled Michele and Grant use for freighting their gear to and from work. I rigged the sled with three harnesses, and we man-hauled two loads up the snowfield to a heli landing site! You can’t really experience Antarctica without walking a mile in the shoes of the early explorers, and we got to walk several miles in them. I don’t think I want to set out for the pole in the footsteps of Scott!

Click on the images below for a larger version.

|

|

|

|

|

|

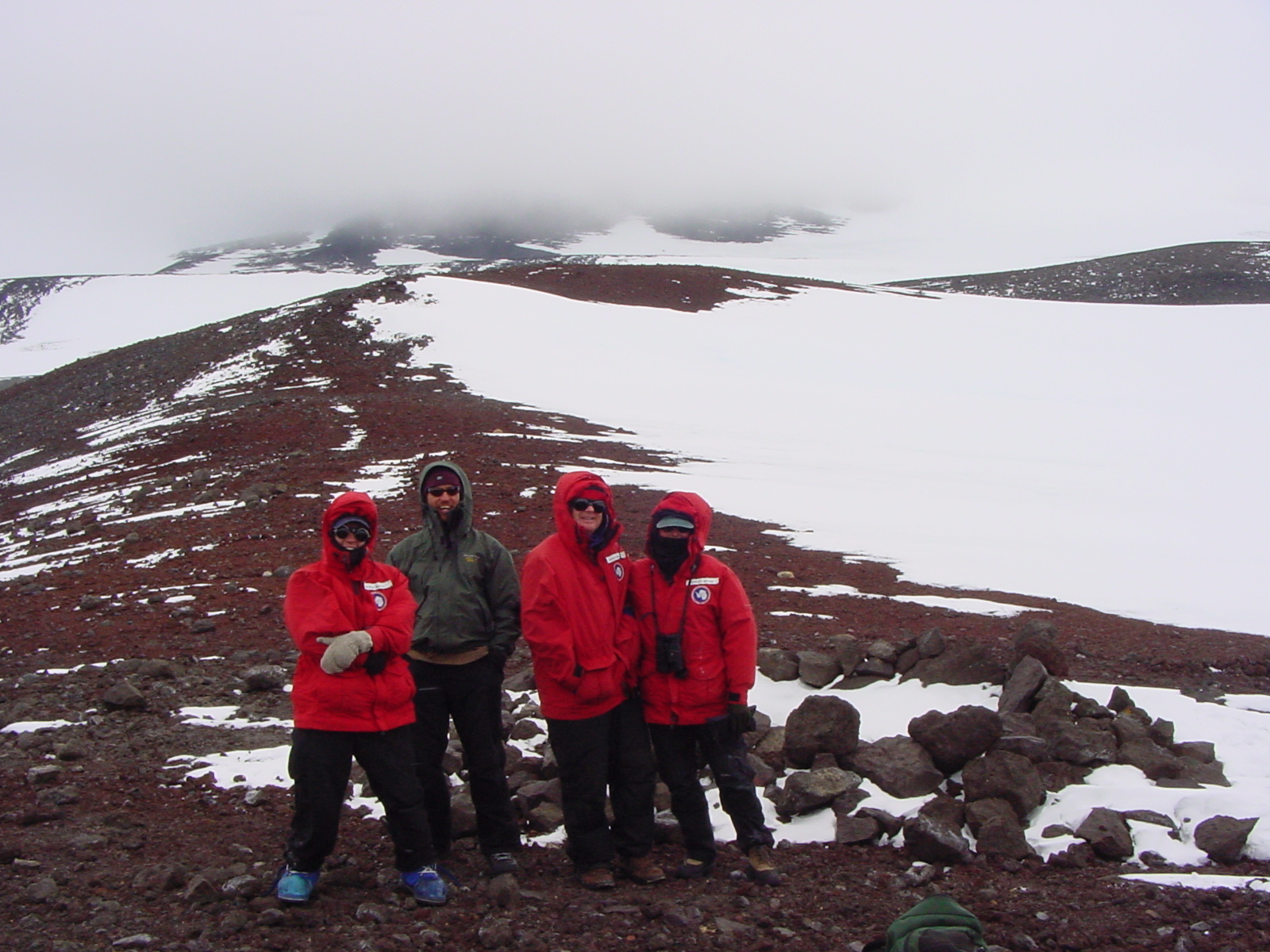

Above: Crevasses on the side of Mt. Terror during the flight to Cape Crozier. The Ross Ice Shelf stretches into the horizon past the Cape Crozier colony, and the middle part of the colony, activity near the shore. Inside the Cape Crozier hut, and gooey ornithogenic deposits in the modern colony testpit.

Steve found an abandoned site high above the modern colony, and we excavated a second test pit there. The sediments started out dry and screenable, but quickly became saturated and another hand-carrying session of heavy sediment bags was necessary. But in a single day we had completed our mission for Point Crozier, which meant we had a day for recreation before moving camp across the island to Cape Bird on the eastern side of Ross Island. Steve learned from Grant that the “igloo” that was constructed by Wilson’s party was but a five mile walk from the hut. This party was dispatched by Scott during the winter of 1910-1911 to gather Emperor penguin eggs for museums in Britain, thought at the time to shed light on the evolution of birds, for what could penguins possibly be but the ancestors of flying birds? This journey became known as “The Worst Journey in the World” as described by participant Apsley Cherry-Garrard, when the three participants spent the winter on a grim, wind-blasted point, in a tent reinforced by piles of rocks (the igloo), collecting Emperor skins and eggs to finally transport back to England where the curator said “thanks” and stuck them on a shelf in a closed room! Grant had been to the site before, and we were all psyched to visit another Antarctic historical landmark. The hike stayed high along moraines, avoiding glaciers and all but a few snowfields, but as we traversed closer to the igloo we faced more directly into the rising wind. By the time we reached it, the wind was a gale, the last snowfield a whiteout, and the wind chill had become severe. It was exactly the conditions the three men had experienced for months, only about 70 degrees warmer! We took photos of the hut and each other, including the shots (below) of some of their supplies and penguin skins they left behind when they finally departed for the base. Again, it was a mute testimonial to the amazing endurance and toughness of the early explorers. We thankfully turned downwind and headed back to our much more comfy temporary home.

The next day we were due to fly to Cape Bird, but the weather was not cooperating. Things were evidently much worse in McMurdo, so the helos were grounded and we were staying an extra day. Not a bad place to be stuck, the delay allowed us to check out what modern penguin research is all about. It is incredible what a couple of days spent with Michelle and Grant taught me about penguins and what they are capable of. If I was impressed by their hilarity at Marble Point, I am now humbled by their supreme adaptability to this harsh land. First of all, how does one study penguins? A critical tool is the “weigh bridge” and its enclosed colony. A snowfence is erected around a sub-colony, with the only way in or out for penguins being crossing an electronic scanning “bridge” that these clever birds figure out in a heartbeat. Grant said many start crossing the bridge before the fence is installed! The birds are then tagged with an injected barcode, and every time they cross the bridge they are weighed and their trips recorded. The “weigh bridge colony” serves as the control for the most detailed parts of the research. Other birds are provided with a variety of instrumentation: time-depth recorders for dives, satellite tracking devices, and various telemetry tools, all attached with tape (but one very expensive unit was lost while we were there, provoking a detailed review of taping techniques!). Chicks are captured, measured for wingspan and weight, and returned to the nest often before the parent notices. Leopard seal watches are conducted to study predation, and young adult birds are banded- 1000 each year. It’s quite a task, and these two work long days throughout the season to complete their yearly study before winter comes. So what have they learned about Adélie penguins? For one thing, they are excellent parents. While one watches the chicks, the other rapidly descends to the sea along a series of predetermined penguin superhighways to gorge on krill, spending anywhere from 15 to 24 hours away from the nest before returning to feed the chicks. During this time they have been avoiding leopard seal attacks, travelling hundreds of meters vertically between the nest and the sea, and diving as deep as 150 m to feed! Their dives are lengthy (much longer than the animal physiologists claim they can be), and the time spent on the surface to recover miniscule. They are little fireballs of energy and stamina. Their swimming technique is perfect; they are so hydrodynamic that their frictional drag cannot be measured! And they can alter their body shape while swimming for greater streamlining and to execute more demanding manuvers. Amazing birds, and far from the Victorian assumptions of having a pleisiomorphic, or “primitive” body plan, these animals are supremely derived and adapted for their life in the sea and on ice and land!

As it turned out, we never did get to Cape Bird, the weather did not relent and we had our coldest night so far, minus 10 degrees C. Finally, a weather break on Wednesday allowed a quick pickup and return to McMurdo. Mike has been a workhorse, wetscreening sediments in the lab, but for this go round the materials were too smelly for indoors, so he wetscreened outside in temperatures well below freezing! Tomorrow I visit the food room to load up for another field trip, this time to Capes Hickey and Day- our most remote destinations this season. It’s very exciting and perhaps a little scary to know we are going out to the limit of helicopter range, especially since the weather has been so inconsistent. I’m certainly packing food for extra days!

I’ll write another update in a week or so when we return.

Click on the images below for a larger version.

|

|

|

|

|

|