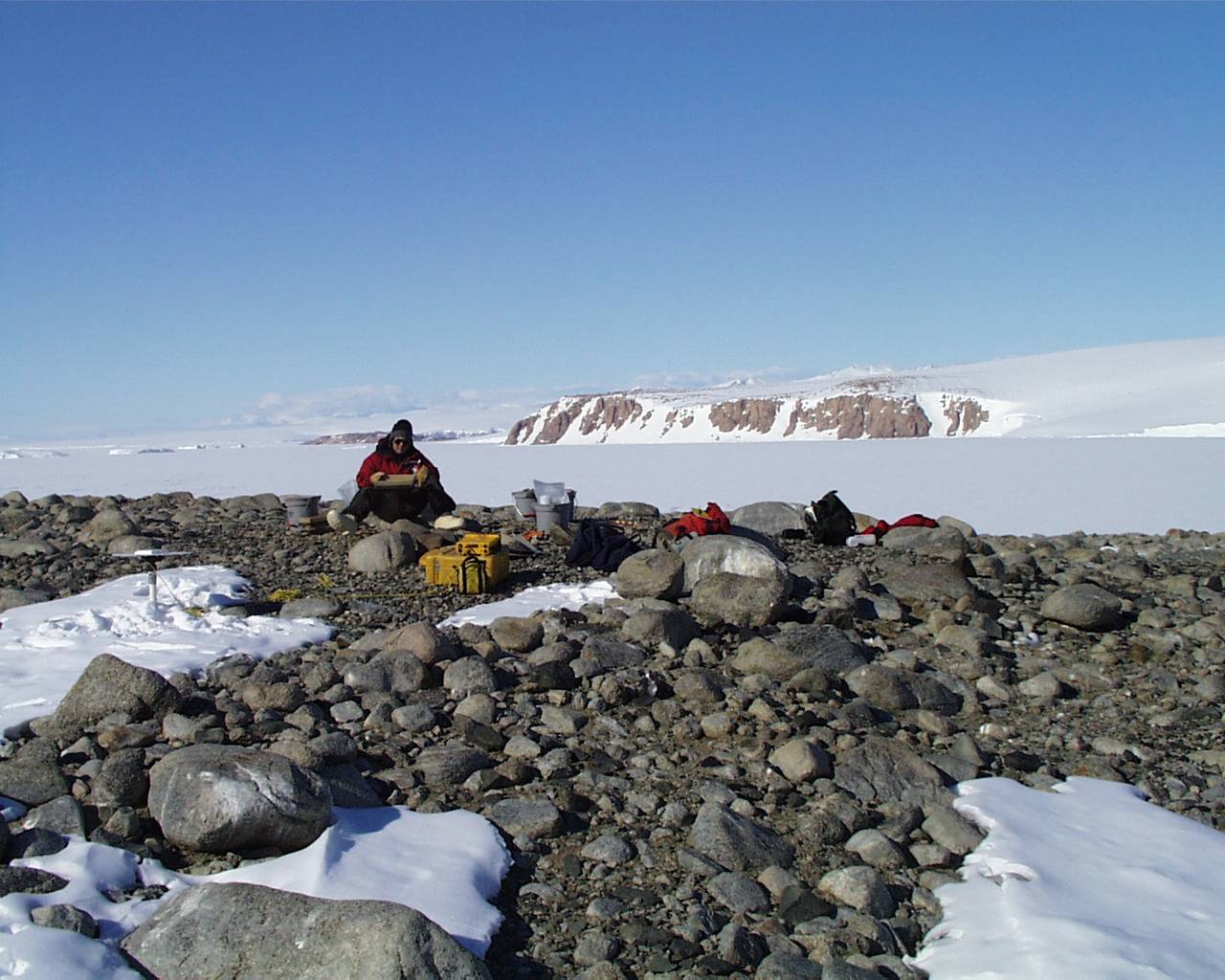

Camping at Cape Ross

One skill necessary to be a successful P.I. (principal investigator) in Antarctica is the ability to think quickly on one’s feet, and Steve got the chance to demonstrate that skill on our last field outing. The flight out to Cape Hickey was a complicated and involved operation. A refueling stop was necessary at Marble Point to maximize the Bell 212’s range, and our camping and excavation gear was tightly packed into the interior of the ship, instead of in a slingload, at the pilot’s request to maximize airspeed and to minimize fuel consumption on this extended flight. As we rotored northward along the coast an unusual sight appeared in the sky, a jet contrail. Anywhere else in the world this sight would have raised no comment, but crossing the Antarctic continent is on the flightpath of no commercial airliners, so this must have been a military flight, and the shadow cast by the contrail painted an ominous black swath across sea ice and glaciers that we crossed through it on our way north.

We flew over mile after mile of desolate coastline, with huge glaciers spilling out in enormous ice shelves to become one with the continuous sea ice. The only dry land appeared very infrequently in the form of tiny capes punctuating piedmont glaciers or bounding ice streams. We flew over a couple of promising sites, Cape Ross being noteworthy for its exposed beach terraces and level surface. Passing Cape Day, south of the Mawson Glacier, the site we intended to move our camp to in a few days, we noted that it appeared buried in fresh snow. Finally Cape Hickey came into sight, and its appearance could hardly have been less reassuring. A tiny wind-blasted point jutted out into the frozen sea, surrounded by monstrous glaciers that isolated it as perfectly as an ocean isolates an island. The entire point was covered by snow, with only hummocks of glacially scoured rock sticking through. I felt my heart sink as I pondered the safety of our small group in such a place, especially considering how likely it was for storms to prohibit flying to such a remote destination. Even now the coast just north of us vanished into the fog and spindrift of an approaching storm, causing the pilot to remark he was glad he wasn’t flying any further north with us. I considered insisting that I could not assure our safety in such a spot, but it was the snow cover that really helped Steve make up his mind about Cape Hickey. He hopped out of the ship for a quick look around, and returned to tell us that the sites were too buried in snow to locate, and there was no point in being dropped off there for possibly days before we could be picked up, unable to work. He requested that the pilot fly us back to check out Cape Ross more closely, and possibly change our plans to work there instead. As the ship got ready to lift off, and I was still pondering the inhospitable and unfriendly nature of this spot, we spied movement off the seaward side of the helicopter. Two Emperor penguins slowly paddled by across the snow; curious about what this strange thing was that had suddenly appeared on their home turf. It suddenly hit home for me what the lifestyle of these largest of the penguin species demands of them, as they spend their entire lives out on the sea ice and ice shelves, never setting foot on land. All during the dark, frigid winter the breeding birds balance an egg on their feet to keep it off the ice, as contact would instantly freeze it, and thus do not eat or move during that entire time. This spot that I found so frightening for its cold, desolation, and harshness is simply home to these incredible animals! This demonstrated to me once again the incredible adaptations that these fascinating creatures had undergone to master the Antarctic environment.

Orbiting Cape Ross, we noticed that a field party was already there. The pilot knew their science team number, but not what kind of project they were working on. After landing, Steve ran over to make sure there was no problem with our working in the area as well, and found that geologist Brenda Hall and team were working on dating the exposed beach terraces that were prominent on the point. We were welcomed to share the point, and we quickly unloaded and pitched camp on Cape Ross.

Raised beach terraces, such as this pronounced one on Dunlop Island, are an important part of Steve’s work too, as ancient penguins chose these high points for nest sites, and radiocarbon dates on penguin remains provide minimum ages for the exposure of these terraces. Much work has been done and is still underway interpreting the mechanism and timing of the formation of these terraces. The best supported hypotheses suggest that at the end of the Wisconsinan glacial maximum, as the ice sheets retreated and the heavy load of ice was removed from the coast the land began to rise, or isostatically rebound, from its overburden of heavy glaciers. As isostatic rebound occurred, a series of beach terraces was formed, stairstepping downward to the present-day sea level. Brenda’s group was working to establish absolute dates for each terrace level, and previous work had indicated an age of 7600 yr B.P. for the highest terraces at Cape Ross (Conway et al., 1999). As a part of our work, we precisely measure the elevation of our terrace sites above sea level using highly accurate Global Positioning System (GPS) equipment, as visible in this shot of Mike screening at Test Pit 2 on Cape Ross.

Our work at Cape Ross progressed quickly, with our crew excavating three test pits in a day and half, and then Brenda offered a suggestion that we visit Dunlop Island on our way back, as beach terraces are abundant there and her team had encountered abandoned penguin sites as well. We had a camp move scheduled, originally to Cape Day, and we now changed our destination to hit Dunlop Island on our way back down the coast, as it lies just a few miles north of Marble Point. Rob, the Kiwi pilot, arrived early to pick us up on a beautiful warm and calm day, and we moved camp to a flat area near the middle of the island. Like Cape Ross, Dunlop Island was remarkable for numerous exposures of beautiful white granite, shot through with startling jet-black intrusive dikes. The entire island was only a few kilometers long, and we were able to survey it thoroughly. Steve located promising sites on the highest terraces, and we excavated and then backfilled three test pits. Most notable at Cape Ross and on Dunlop Island was abundant evidence of what a desert Antarctica truly is, regardless of the amount of snow and ice. The basin in which we pitched camp was a playa, much like you would see in Death Valley; complete with crusted salt deposits on the surface. On all exposed rock surfaces is visible the effects of sandblasting by the wind, and weird ventifacts (rocks shaped by wind abrasion) such as this one are common. Much of Antarctica is reminiscent of the Black Rock Desert, only covered with glaciers! And again evidence of the remarkable desiccating preservation of this environment became apparent. We found the mummies of two Weddell seals inland on the island, including one that had been tagged by researchers in the past. Mike recorded the tag on his digital camera to inquire amongst the seal researchers at McMurdo as to its origin.

Our experiences with Emperor penguins were not over either. As we surveyed the island, Steve spotted two molting birds standing on the ice 50 m or so offshore. He explained that molting requires so much energy that the birds pretty much stand still during most of the process, much as they do during the coldest months of winter. But feathers they had shed blew across the ice, and we found many around us on the ground. Our pickup by helicopter was delayed, and we spent several hours in the cold wind waiting to hear the sound of rotors. Finally our ship arrived, our 1200 lb. camp loaded into a sling (preferred by this pilot), and we were off to McMurdo. Crossing the edge of the sea ice, in a small area of open water, I noticed a disturbance in the water. Suddenly a geyser of spray erupted upwards, and I realized that a small group of Minke whales was feeding around the ice edge. We arrived back in “Mac Town” at 11:00 PM due to our late pickup, and after unloading our gear at our storage cage, we hit the bunks for some needed rest.

Our next trip takes us to another active colony at Cape Bird, optimistically with a camp move mid-week to Cape Royds, the site of Ernest Shackleton’s historic hut, then back to McMurdo by week’s end. After that, we have only one camping trip left before the helicopters shut down for the season. I will write another update after our next trip.

Reference Cited:

Conway H., Hall, B. L., Denton, G. H., Gades, A. M., and Waddington, E. D., 1999. Past and future grounding-line retreat of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Science 286, pp. 280-283

Click on the images below for a larger version.

|

|

|

|

|

|

.jpg)