Camping at Cape Bird & Cape Royds

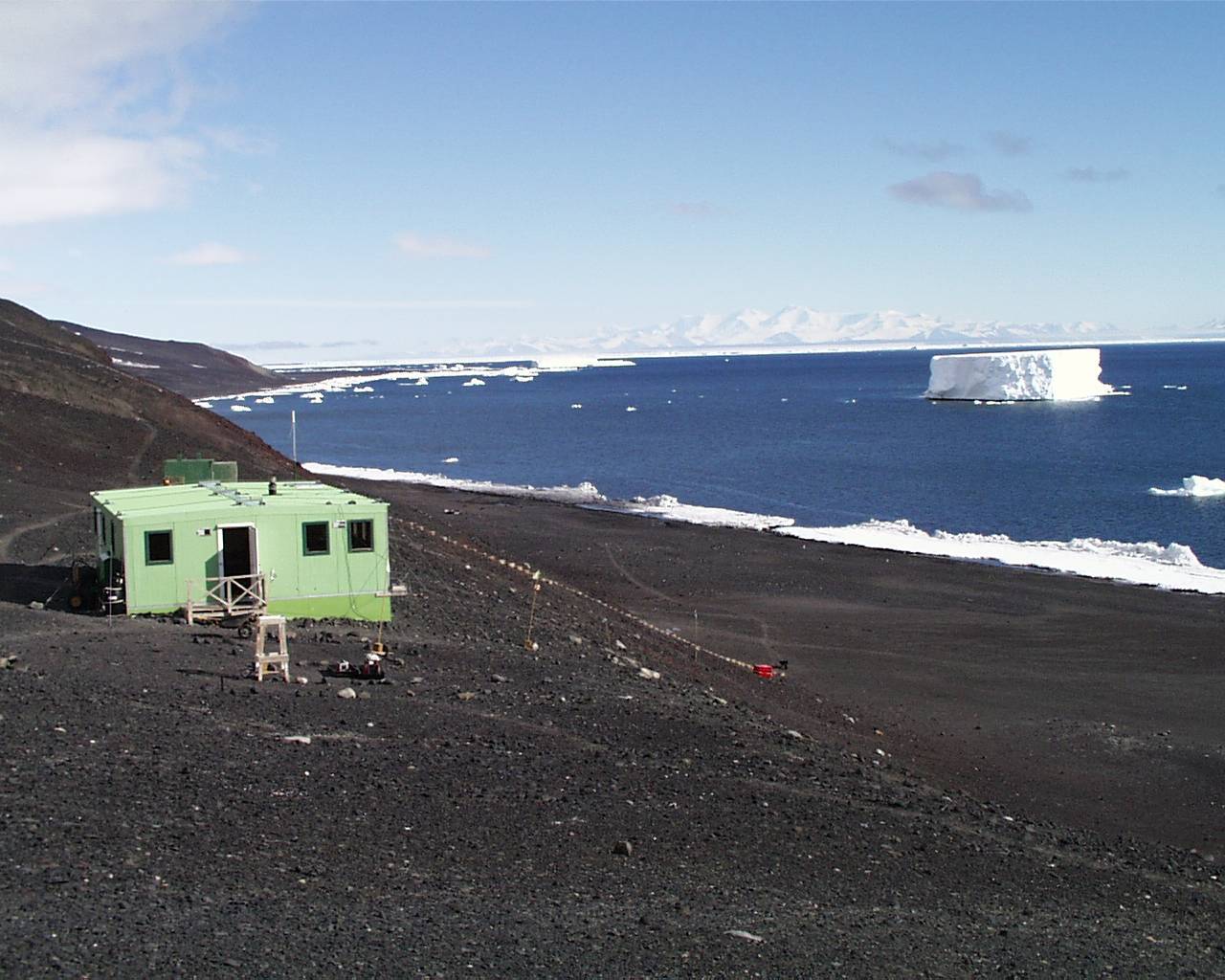

On the helicopter ride up to Cape Bird, it quickly became apparent why getting in and out of Bird can be such a problem for the helos. The pack ice was broken up just past Cape Royds, and the ship had to make a big detour up over the shoulder of Mount Bird to avoid flying over open water around the final fjord before Cape Bird. We were in helicopter “Hotel November Oscar”, the Kiwi ship, and Rob confidently climbed up over lingering clouds and fog, then dropped precipitously down a sharp ridge to the narrow landing site on the beach, thus minimizing disturbance of the colony. We were met at the landing pad by penguin researchers and hut occupants Carey Barton and Jaqueline Biggs, a pair of Kiwi women who were spending the field season at this second largest of the Ross Island Adélie colonies. Once again we were informed that we wouldn’t need our camping gear; there was plenty of room at the hut and we were welcome to stay there. We grabbed our personal gear and food boxes, and with help from Carey and Jaqueline we headed down the beach and up the hill to the New Zealand Cape Bird hut. Calling this palatial structure a hut is a bit of a misnomer, more like a holiday cabin I would say. It is over four times as large as the Crozier hut, and equipped with bunkrooms, a water storage tank, and a shower (if you are willing to heat the water on the stove and then carry the gray water down to the sea!). And the view out the hut windows was spectacular; better even than the view from the Crozier hut. The sea is open along the north coast of Ross Island, and the sea ice had melted off the shore so there were miles of black sand beaches exposed with waves gently lapping the shore. Offshore, huge otherworldly icebergs drifted past, sometimes large enough to block off the entire horizon. At the eastern terminus of the beach, a lobe of the Bird Ice Cap calved into the ocean, presenting a massive serac that cracked and groaned as it adjusted to its eternal downhill journey. The colony itself was divided into three major sub-units, with the largest, the Northern Rookery, just north of the hut. The Cape Bird weighbridge colony (see Update 3) was in this sub-unit.

We had two objectives at Bird: the first to obtain another sample of modern penguin deposits for comparison to fossil ones and to compare between modern colonies, and the second to sample fossil deposits in the area. Cape Bird was ideal for Steve’s work because of the juxtaposition of modern deposits to fossil mounds. The present colony mounds were stained red from the guano of the birds, and alongside these mounds were dark pebble mounds that revealed red soil layers with a scrape of the trowel. We sampled a modern deposit in the center of the main Cape Bird colony, and Steve was surprised to find a buried ornithogenic soil layer more than 40 cm down in the deposit, beneath a layer of sterile sand. It appears that an older colony was disrupted by some sort of depositional event, probably glacial expansion due to the proximity of the Bird Ice Cap, and then later colonization resumed and continued to present. It will be very interesting to radiocarbon date the earlier occupation. As at Crozier, the sediment bags had to be carried out of the colony to the helo pad on the beach, so I spent the better part of the day freighting heavy packs through the colony and down the beach, assisted this time by a wheelbarrow owned by the Kiwis.

Click on the images below for a larger version.

Above: Pack ice on the flight to Cape Bird, and the beautiful Kiwi hut. Icebergs drifting by Cape Bird, and the snout of the Bird Ice Cap calving into the Ross Sea. The Cape Bird Northern Colony with Beaufort Island in the distance, and excavating fossil mounds adjacent to modern subcolonies.

One site that Steve was very interested in sampling was in the south end of the middle colony. This site had been tested by New Zealand researchers, and an exceptionally old deposit had been found, yielding a radiocarbon age of 8,080±160 yr B.P. on bone (Heine and Speir, 1989). These two apparently found this old deposit under a sterile gravel layer, 44 to 52 cm deep in the test pit which eventually bottomed at 85 cm (Heine and Speir, 1989). Steve was easily able to relocate the elongated mound where this deposit had been sampled from their excellent description, and we dug a test pit. This pit went down through a relatively thick layer of ornithogenic soil, then hit sterile sands and eventually permafrost at about 60 cm. Again it will be very interesting to see what this deposit dates to, as 8,000+ years is a very long time for occupation of a colony, and may tell an interesting story about the annual removal of sea ice in front of Cape Bird. We returned to the Northern Colony and dug one more test pit, moved all the sediments to the helo pad, and we were finished with our work at Cape Bird. We retired to the hut to cook dinner for our Kiwi hosts in partial repayment for their hospitality. Our schedule called for a helicopter pickup and camp move to Cape Royds the next day, thus allowing us the chance to sample all three of the largest Adélie colonies on Ross Island.

During the night a thick layer of fog rolled in from the north and west, and in the morning we got the word from McMurdo that pea-soup conditions existed there as well, with one helicopter “finding its way in by Braille”, and another stranded at Black Island, waiting for improved visibility to return to base. Our camp move was on hold for better weather, and thus we spent another day at Cape Bird amongst the penguins. These delays have proven fortunate for increasing my understanding of the ecology and biology of these amazing birds. The exposed black sand beaches gave evidence of how abundant krill is in these waters, which serves as the almost exclusive food source for the Adélies. A bright red line of these tiny crustaceans stained the beach for miles at the highest reach of the waves. The rapidly growing penguin chicks had begun to form cohorts, called creches, for safety and companionship while the parents were away for extended periods feeding and bringing back food for the youngsters. The adults continue to feed the chicks, who by now are demanding a huge amount of regurgitated food for rapid growth rate they are experiencing. Soon the chicks will be ready to hit the water and begin to forage for themselves, as evidenced by the molting of the downy gray feathers for replacement by adult plumage. These adolescent birds lose the cuteness of chicks and look comical in a partly molted state, for which Steve coined the term the “Beethoven look”. (By the way, Steve is not just randomly handling penguins! He assisted the New Zealand researchers with chick banding- a formidable task that is undertaken late each season to flipper tag 1000 chicks per year for follow up of cohorts.) And always in evidence is the complex social interaction of the birds, as exemplified by this “ecstatic display” between a returning parent and its mate. The interaction between skuas and penguins is complex and somewhat brutal as well. Pairs of skuas have staked out territories near sub-portions of the colonies, and when smaller chicks stray too far from safety they may suddenly be snatched up and become part of the skua’s diet.

Another night spent with the Kiwi women was pleasant as well, and allowed me more insight into New Zealand culture and their unique twist on the English language. Jaqueline and Carey educated us on the finer points of the distinction between Vegemite and Marmite, and explained that no one likes both (Jaqueline prefers Marmite and Carey is a Vegemite aficionado) and that preference for one or the other is apparently passed down through families over generations, and may even affect compatibility for marriage! Surprising to me was their extensive knowledge of U.S. culture, politics, etc. They knew about the latest happenings (or at least latest as of late fall when they arrived on the continent) on Opra, Letterman, and Leno, and could speak with authority on the various American movie stars and celebrities. They had followed the election debacle with interest, and spoke with great insight about the records of the two contenders, the nuances of the Electoral College, and the past history of elections in the U.S. They would have made excellent voters, and indeed we decided that they should be able to vote in American elections, as America’s effect upon world issues is so powerful.

Above: Juvenile birds in creches at Cape Bird, and a parent feeds a hungry chick. Steve holds a chick sporting the Beethoven-look during wellness check, and a skua pair lurk outside the colony, occasionally snagging an unwitting chick. The Cape Royds colony below the Mt. Erebus.

By morning the weather had cleared, and by 9:00 AM our helicopter could be heard coming over the shoulder of Mount Bird. We sling-loaded our camp for the short hop to Cape Royds, and set down next to the polar huts of the penguin crew studying the Royds colony. There we were greeted by Sophie Webb, the researcher who has spent the last four seasons at Cape Royds, and were invited to share kitchen facilities. This meant that we only had to pitch sleeping tents, and we completed this task in a brisk wind, making it unusually challenging. We grabbed our excavation tools, and headed down to the Cape Royds Colony to obtain a final modern sample. Sophie explained that Royds is unusual in relation to the Crozier and Bird colonies in that these birds have occupied the most marginal of sites available for colonization, due to its southern location and the fact that on colder years (like the current season) the sea ice margin may be far away to the north. These birds are truly living “life on the edge” of penguin existence, and we hope for some interesting results from our analysis of these sediments. Another reason that Steve wished to visit Royds was to visit the hut that Ernest Shackleton built during his attempt on the South Pole in 1908-1909. Like all the Ross Island huts, this one has been maintained as a living museum with many artifacts and furnishings still in place from almost one hundred years ago. It is awe-inspiring to enter this well-built structure and to view items of daily life used by these early polar explorers. My admiration for the golden age heroes of Antarctica continues to grow.

Our final goal for Cape Royds was to traverse a few miles south to Cape Barne and sample some abandoned sites there as well. The hike took over an hour across the small bluffs above the sea ice, and after a bit of searching we located the telltale pebble accumulations of fossil penguin mounds. The first test pit at the Cape Barne site was perhaps the richest we have found this season, as evidenced by this mummified penguin chick that was uncovered 15 cm down. We excavated another less productive test pit, and packed our samples and tools for helo pickup the next day. We flew back to McMurdo next morning, and dragged our heavy sediment bags to the lab. This trip finished our extended camping missions. From here on out we will be making helicopter day trips to various sites for survey and quick sampling if feasible. One exceptional opportunity that has arisen is the chance to board the Coast Guard icebreaker Polar Sea for a two day cruise up to the northwesternmost extent of the Ross Sea to visit Cape Hallett where there is an important site discovered by the Italians. This trip should be exciting, with lots of views of sea life along the way, and an overview of the coastline for future research projects. I will write another update after several helo trips or the Polar Sea journey.

Reference Cited:

Heine, J. C. and Speir, T. W., 1989. Ornithogenic soils of the Cape Bird Adélie penguin rookeries, Antarctica. Polar Biology 10, pp. 89-99

.jpg)