Steve's polar visit, Cape Crozier, and the last Scott Coast survey

The week began with a little extra excitement for Steve. It turns out that the seats were extremely limited on the boondoggle flight to the South Pole, so only Steve got the chance to go. He boarded the bus for transport to Pegasus at just before 6 PM, and then was southbound on the Herc a couple of hours later. For the first third of the flight Steve's plane followed the Transantarctic Range south of our familiar Scott Coast, and he shot photos of dramatic glacial terrain carved by the ice descending from the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS). He saw several fascinating dry valleys, similar the McMurdo Dry Valleys, where one could walk around and explore without facing the dangers of glacier travel. But soon thereafter the plane edged onto the EAIS itself, and the terrain became a uniform flat, white, featureless landscape that persists all the way to the Pole and beyond. His camera had trouble focusing on the surface below because nothing stood out as a clear point in the vast ice sheet. Soon they arrived at the South Pole Station, and were given only a half hour of ground time while the fuel the Herc carried in was unloaded. As he stepped off the plane he was struck by how sunny and balmy it appeared to be, so much so that he pulled off his balaclava to enjoy the nice day. But only a few yards later he noticed his face was becoming frost nipped- temperatures below -30°C are serious, even when the air is still and the sun is intense. Steve just had time to visit the ceremonial and geographic South Pole sites (we are both confused about the need for a ceremonial South Pole), and did a quick walk-through of the new Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. One of the more bizarre things he saw was the greenhouse, full of lettuce, herbs, and salad greens to freshen up the galley cuisine- an odd, colorful sight in an otherwise bleak place. Then it was time to re-board the LC-130 for the return flight to Pegasus, and Steve was back to our dorm by 3:45 AM.

In an extraordinary coincidence, and as quite the bonus for his trouble, one of Steve's fellow passengers on this flight turned out to be none other than Falcon Scott, the grandson of Sir Robert Falcon Scott, the Antarctic legend. Falcon was invited by the Antarctic Heritage Trust to help in the rehabilitation of the Terra Nova Hut at Cape Evans- the amazing hut constructed by his grandfather and expedition members in 1911 for their successful (and fatal) push to the South Pole. Since the 100th anniversary of their arrival at the South Pole on January 17th, 1912 occurred this season, many commemorative activities have taken place, including one with Falcon at Scott Base and the Cape Evans hut. But now he was visiting the Pole for the first time, and Steve could only imagine what was going through his mind as he looked down at the place his grandfather died and is still entombed in the ice of the Ross Ice Shelf. He has expressed great satisfaction at the work in progress at the Cape Evans hut to preserve his grandfather's legacy for future generations, and it must be amazing to have such a close connection to the heroic-age events that now form the basis for all activities in the Ross Sea today.

Click on the images below for a larger version.

Steve visits the geographic South Pole on Jan. 24th, 2012 (left), and the dejected members of the Scott party arrive at the Pole on Jan. 17th, 1912 to find a tent left by Amundsen five weeks earlier (right).

Since Steve was rather tired from his all-nighter visiting the Pole, Tao, Jurek and I geared up for a day trip to Cape Crozier. Although I doubted there would be deep sediments for Tao to sample, he wanted to take a look, and Jurek wanted to further investigate some lakes that lie above the far-flung southeastern sub-colony. We arrived at Crozier in a brisk wind, and found it snowier than I've ever seen it. Our A-Star pilot Chris warned that if the wind stiffened we should let Helo Ops know since they can't fly out here if the winds get above 40 knots. We changed into field clothes and Jurek headed out on the high route while Tao and I dropped down the northern edge of the colony. As I suspected, Tao was disappointed with the depth of the sediments, but gamely set about collecting a couple of short sequences from exposures along the sides of some pebble mounds. I went down to the beach to shoot some video- a few goals I've set are to record film of penguins porpoising and chicks fledging, neither of which were fulfilled this visit. But I do think that some of what you'll find below will provide insight into the amazing feeling of visiting a colony of over 200,000 nests (modern remote sensing makes us more confident about those numbers than ever before), and the furious activity that is involved in raising healthy chicks to maturity in the brief window of Antarctic summer. I stood alone on the beach for some time, filming and just enjoying how masterful these birds are in their aquatic environment. The heavy surf and shorebreak was no problem for them, as they surfed in and dove under the curl to go out. They are as at home in the water as songbirds are in the sky.

Video: Panoramic view of the Cape Crozier Colony (circa a quarter million birds).

Video: Adelie penguins on iceberg and porpoising.

Video: Furious activity at the beach as Adelies enter and exit the water.

Video: the penguin superhighway that leads from the central colony to the beach.

Video: an almost-adult Adelie sports a mohawk of down.

Video: a banded bird at Cape Crozier- this is how the bird biologists keep track of individual penguins.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adelies sunbathe on the beach at Cape Crozier, and Tao samples a short profile in the colony. The colony along the beach and the Ross Ice Shelf dwarfs the SE sub-colony. A zombie chick pleads for brains as it arises from the ground and sunny, warm conditions at the Crozier hut.

Since Jurek was beyond a high ridge from the main colony, we had lost communication early in the morning and still had not been able to talk by radio, so I hiked up to the top of the ridge to make contact. I enjoy this lofty spot as it provides an unequaled view of the Ross Ice Shelf stretching off into the distance. Jurek was already on his way back to the colony via a high saddle, so we met up as he descended an icy snowfield. We traversed through the colony looking for eggshells for Steve to sample for isotopes, and began climbing back towards the Crozier hut. At the top of the colony we ran into a group of carpenters (Carps) from McMurdo who were there to close down the hut for winter and were taking a break to look over the colony. They had lots of questions about penguins, and were somewhat alarmed by the aggressive skuas they had encountered on their way- I find it funny that they don't bother me a bit anymore, but they terrorized me in the same way my first season. As we traversed through the skua territory we found the goldmine of eggshell remains- skuas had discarded leftovers all around their nest sites so we quickly found plenty of samples. We also passed through the penguin chick mummy graveyard I've mentioned before, where Jurek spotted a zombie chick struggling to return to the land of the living. A sunny day with now light winds made the short wait back at the hut for our helo pleasant, and soon Chris called to ready us for pickup. We made the short but scenic flight back to McMurdo high along the flank of Mount Terror and were soon back in town.

Video: helo flight from Cape Crozier, over periglacial ground and past Tarakaka Peak, with the Ross Ice Shelf stretching off in the distance.

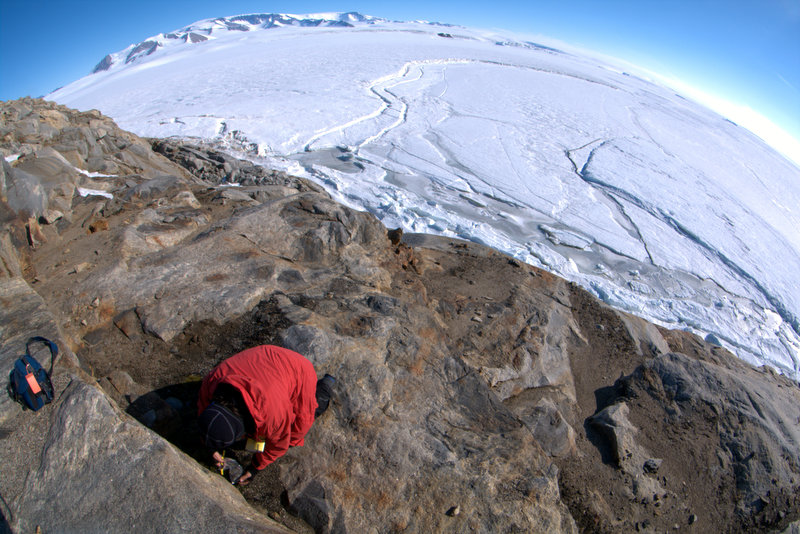

The next day we took our last trip up the Scott Coast with close support, and were pleased to find that Paul would be flying us in the A-Star. Through a detailed study on Google Earth I had figured out that there was one last patch of ground we had not surveyed along the coast, named Tripp Island. Tripp was a bit beyond Cape Ross, and north of it the only exposed ground is found at Cape Day, Cape Hickey, and Prior Island- spots we had already surveyed and excavated important test sites. Paul's remembrance of Tripp Island was that it was very rugged, and we thought it most likely would not contain traces of past occupations. But as we rounded the Evans Piedmont Glacier that brackets Tripp Bay, we found that the island looked rather interesting. Paul did a quick orbit around the island, and set us down on a small snowfield on a small peninsula jutting southeast. I first went out onto the peninsula checking for sites, and admired the convoluted metamorphic rock (gneiss), shot through with jet-black mafic dikes. I also spotted a very mature-looking skua chick pestering its parents with requests for more food. Steve radioed to say that he had found a site, up on the very summit, so I grabbed the excavation gear and headed up. It was remarkable he had found the site- the surface of the island was severely disturbed by glaciation and freeze-thaw process, so the hint that this accumulation of pebbles was ornithogenic rather than geologic was very subtle. But it clearly was a pebble mound, with sediments appearing to be very old (indicated by a whitish rather than reddish color) and containing eggshell fragment. I pushed on up the summit ridge and found one other, similar site. From my perusal on Earth, I had guessed that if sites existed they would be on the northern flank of the island, surrounding a small pocket beach that would allow access through the cliffs. But I found no sites (or failed to recognize them in their disturbed state), only a survey marker that I assume dates from the Navy-era. I pointed out some moss-covered ledges to Jurek, and admired the views of Mt. Endeavour off to west on the crest of the Transantarctics.

Video: an almost-mature skua chick on Tripp Island implores his parent for more food

Tripp Island from the A-Star, and Steve and Paul at the landing site. Beautiful gneiss on Tripp Island, crosscut by black, mafic dikes. A Navy-era (?) survey marker on Tripp, and Jurek collecting mosses on the north side. The unusual occupation site on the summit, and a dark sill form steep cliffs on Mount Endeavour to the west.

Steve excavated the shallow summit site, recovering just enough material to date (we hope), and soon we packed up for a move to Gregory Island. We wanted Jurek to see the vegetation there, and after he and I were dropped off, Steve flew back to Cape Ross with Paul to look over that higher bench we had discovered last week more thoroughly (also to recover a dropped trowel!). It was good that he revisited, because far around the bench to the south he found a few large, very well-developed pebble mounds that we had never mapped before. He collected some small samples for dating, but due to the nature of preservation we assume they will date to the Penguin Optimum along with the other lower sites on the Cape. But he also visited the "mainland chasm" described by Gardner et al. (2006), which supposedly contained occupation sites on the highest beach dating to the Mid-Wisconsinan (28,500 years ago). But Steve found beach terraces composed of large cobbles only, and no mounds present on the high beach (and no obvious test pits either). We both found their discussion concerning this site baffling, as there appears to be no evidence of pre-full-glacial occupation here (unless the high site to the north turns out to be that old).

On Gregory Island Jurek got down to business collecting samples while I headed down to the shoreline to shoot some video. I have been trying to capture the soft, eerie sounds that emanate from the sea ice as it rises and falls in response to wave action off in the distance, but I haven't found the built-in microphones in my cameras sensitive enough. By standing on the sea ice at the junction of fast ice and moving ice I hoped to finally succeed. But I was luckier than I thought- as I had the camera recording a sudden snort came from 15 feet away- a Weddell seal had surfaced to hyperventilate before diving down again (sometimes for more than an hour!). The video is not impressive, but turn up the sound to hear the seal breathing, and he's just visible under the thin ice in the center of the screen. The other video conveys most of the sound I was searching for, although the high-pitched squeals are barely audible.

Video: a Weddell seal surfaces for a quick recharge of air

Video: subtle sounds of sea ice moving (turn up the volume)

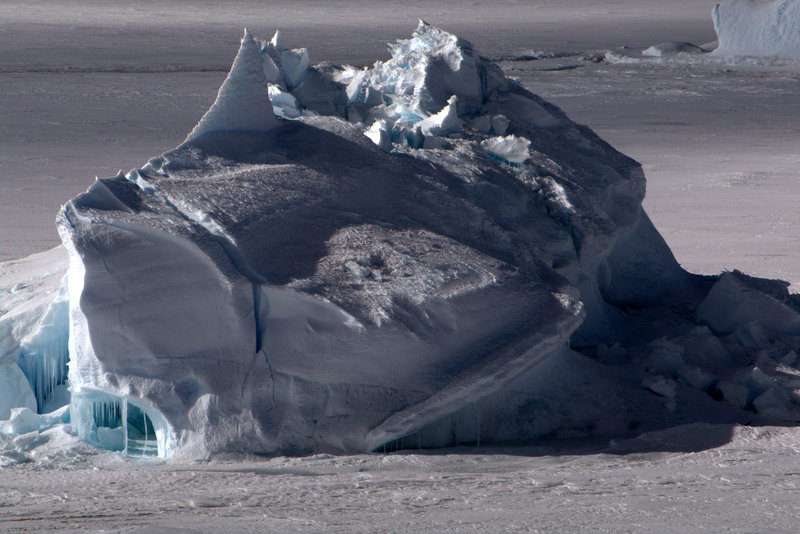

After I entertained myself recording, I climbed back up to higher, northern portion of the island to look around for sites. Both Steve and I were puzzled that there weren't occupation sites on the island, since access to the sea was easy, and it seemed to have terrain perfectly suited to penguins. But even with renewed effort I didn't find a trace- so possibly they don't exist, or possibly they are too disturbed to be spotted. I was again struck by the density of vegetation on the island (we joked about banana and palm trees there), and in several spots I found moss draped from ledges onto the vertical cliffs below- a sight that is common elsewhere but like nothing I've seen down here. The views from the summit area of the frozen-in bergs that surround the island were excellent, and the afternoon light made them glow. I circled around the north end of the island, carefully checking for mounds, while on the lookout for historic-era artifacts as well (the summit cairn is possibly old, but we haven't found it mentioned in print). I always hope to discover a fully-laden sledge melting out of a snow bank, but although the benches were perfect for it, none were found. But a large portion of the northeastern part of the island is geomorphically interesting- large cobbles shaped by wave action form a series of raised beaches marching to almost the highest elevation of the island. Since Steve and Paul had returned to the landing site we had only a short time more in the field for this season. I savored the warm day (windless and sunny) as I strolled back to the ship. We finally reeled Jurek in within a few minutes of our departure time, and were soon airborne again and headed back. But Paul did have enough fuel left for one last highlight- he flew the ice edge all the way back, searching for whales. He has a keen eye for their sign, earned from eight seasons of flying down here, and some that he spotted I couldn't see. But others were clearly visible- with many orca cruising the ice edge, and in echelon across the ice channel. And a few minkes were spotted by Paul's sharp eyes as well. The video below is poor (the autofocus kept catching the Plexiglas), but you can see a few whales at center right. As we neared the end of the ice channel cut by the icebreaker we passed the fuel ship heading back to sea after unloading a gazillion gallons of fuel for the station. We are now working on all the check-out procedures at McMurdo- returning gear, cleaning our lab and rooms, and getting ready to leave "the ice". I'll write up some concluding remarks for a final update later.

Gorgeous (but gritty) red granite on Gregory Island, and Jurek surveys the botany (such as the lichen and mosses below). Two frozen-in icebergs offshore, the rounded cobbles of an uplifted beach on the north shore, and snow stratigraphy apparent on the edge of Evans Glacier on the mainland.

Video: flying the ice edge, with whales visible in center-right