No-go on Cape Bird, three day-trips

Well, after five days of being scheduled for it, and five days of cancellations, our hopes for camping out at Cape Bird didn't work out this season. Flying helos out there is problematic- very similar to the situation we faced at the northernmost cape on the Ross Sea, Cape Adare (see Update #9 from the 2004 season for details on Cape Adare). Weather-wise, Cape Bird juts out into open water, and even though the flight distance from McMurdo is just a little over 40 miles, the visibility there can be dramatically different than here, with coastal fog and clouds obscuring the view. And since it is surrounded by open water, the single route for NSF helicopters to fly in is over the flank of Mt. Bird, followed by a quick drop onto the beach from above (NSF ships are not capable of over-water travel because in the event of engine failure and an emergency landing they would sink like a rock!). So any blanket of low clouds or fog closes out Cape Bird as a possibility- and that happened on all five days we were scheduled to fly last week. Even mornings that were sunny and clear "in town" turned out to simultaneously produce un-flyable conditions to Bird. One further complication for executing a Plan B on cancellation days is the hectic Helo Ops schedule- since our Cape Bird attempts were one-way trips, no flights were available to pick us up if we went elsewhere. But finally, by Wednesday, we managed to fit an alternate plan into the schedule, and when Bird was closed out in the morning, we flew up to Dunlop Island on the Scott Coast as a second choice.

Click on the images below for a larger version.

Cape Bird closed out (left), and open for flights (right).

We had last visited Dunlop in 2001, on our first season down here, and had camped out there for a few days while we worked. Our first goal of our re-visit this season was to relocate our old sites, and survey for sites we may have overlooked last time. The island is quite flat, with the only topography provided by raised beach terraces that reach some 15 meters above sea level near the center. We quickly found our previous test pits on this highest terrace, and determined that we had indeed sampled the most promising pebble mounds.

Dunlop Island excavation in 2001 (left), and the site today.

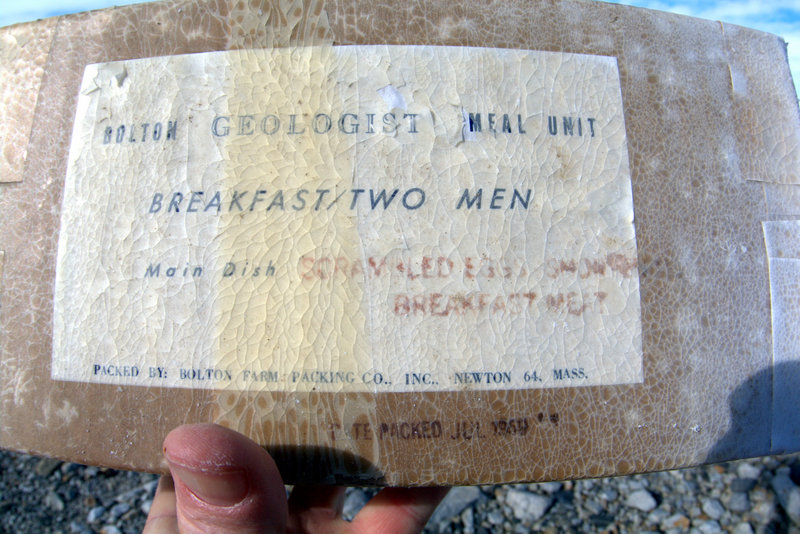

Since we decided additional samples were unnecessary, we headed off to complete a thorough survey of the rest of the island for sites we may have overlooked. Steve and I took off in opposite directions for a circumnavigation while Jurek searched for plants and Tao began probing the sediments in basins that surround the old sites. Although the scenery on the island itself is un-dramatic, it is surrounded by expansive sea ice that contains several interesting frozen-in icebergs, open-water leads, and occasional Weddell seals basking in the sun. After I made it around half the island, Steve called on the radio to tell me about a discovery we somehow missed in 2001. On the southern-most tip of the island he found a food cache evidently left for emergencies from back in the Navy days of the mid-century. The cache consisted of a large box that had probably once been covered with a rock cairn, but was now exposed to the elements and had broken open. Inside were smaller cartons containing a variety of foodstuffs that anyone stranded in the Antarctic would covet (at least anyone from the 1950s)- canned Spam, chicken fricassee, tropical punch, M & Ms, Nescafe, instant mashed potatoes, and of course pickle relish. The Navy-vintage was confirmed by the spent smoke grenade nearby (they used these to determine wind direction and speed during helicopter landings- a practice no longer needed), and the packing date still visible on one carton of 1954.

Frozen-in iceberg off Dunlop Island, and a lounging Weddell seal. The 1950s-era food cache on the beach, a smoke grenade, and some treats for stranded travelers.

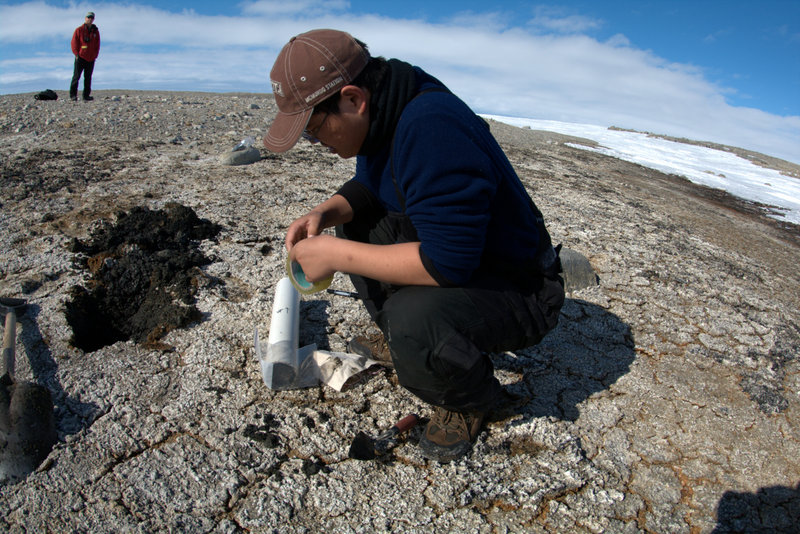

After checking out the cache, and completing my circumnavigation of the island, Steve and I headed back to the high terrace to check on Tao's progress. On the way we passed a rather elaborate stone construction that obviously had housed a latrine for a field party- we suspect it was Brenda Hall's group that had been recovering seal remains from the beaches. Tao had found some rich, organic (stinky) deposits of mud in the shallow basin just north of the fossil rookery, and successfully recovered a short core. A short while later we were boarding the 212 once again, heading back to town in time for dinner.

Over-built privy on Dunlop Island, and Tao sampling organic-rich mud with a short core.

Another day- another scratched mission to Cape Bird. For our alternative on Friday we chose Marble Point- since the helos fly in and out of there all the time for refueling, Helo Ops figured it would be easy to get us a ride home if we were unconcerned about the time. I've commented on my feelings about Marble Point before in postings from previous seasons- during the short-lived effort to build a major base there it has suffered the most human impacts of any region around the Ross Sea (with the sole exception of McMurdo). Bulldozer scars slash the beach terraces, and scraps of lumber, metal, and bamboo litter the ground. But scientifically Marble is important as the southern-most ancient Adelie penguin occupation on the entire Victoria Land Coast, and it was worth one more visit to investigate. Once again I found myself photographing the concentric band of beach terraces, it is the classic example of isostatic rebound elevating the coastline as the burden of ice was removed by glacial retreat. We wandered the point proper southward, and carefully surveyed for occupation sites we may have missed before, but we had already found all there were to see.

A fine, glacially-polished example of the marble Marble Point is named for, and two views of the classic coastal geomorphology exemplified along the beaches. Steve checks out the very southern-most penguin occupation site on the Victoria Land Coast at Marble Point.

A radio call to Helo Ops confirmed that we weren't to be picked up until 6:30, meaning we had many hours ahead of us for the day. Steve and I decided to walk south along the coastline towards Cape Bernacchi until we tired of it, and we then wrapped inland along the front of the Wilson Piedmont glacier, completing a loop back to where we started. Along the way we passed an unusual ventifact of granite, split by white dike. Once back at the survival bags my GPS confirmed an almost 9-mile day of walking- at least a large dinner would be justified! As we waited for Scotty's 212 to arrive, Tao unfurled his expedition flag for photos- the bright colors contrasted sharply with the muted earth-tones of the local geology. Our radio crackled to life as Scotty announced that he would be landing in minutes, and the thumping of the 212's rotors arrived as he rounded the corner from Taylor Valley. He had picked up a passenger from Lake Hoare, along with his camping gear, so the ride back to McMurdo was a bit cramped. But as usual the light on the Royal Society Range was perfect in the late afternoon, and I happily shot photos of the peaks I have shot many times before.

An unusual granite ventifact on the slope above Marble Point, and Tao unfurls the expedition flag. A very crowded 212 on the ride back, and nice views of Mt. Lister in the Royal Society Range.

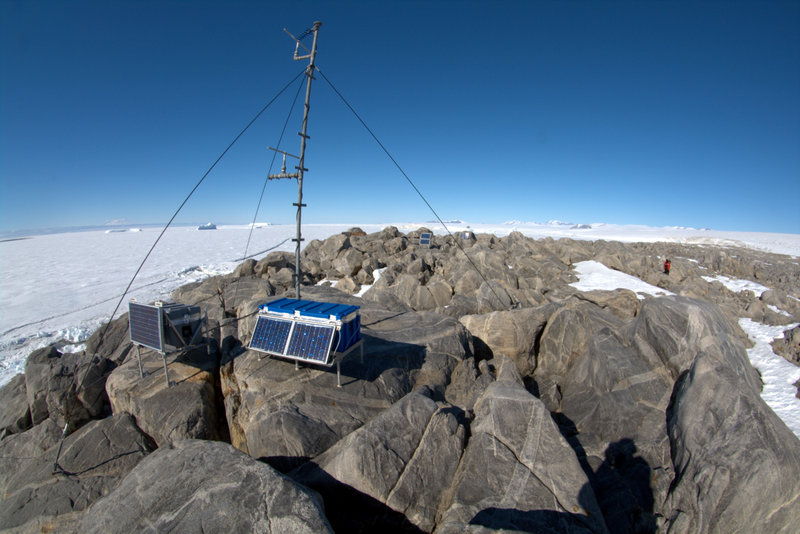

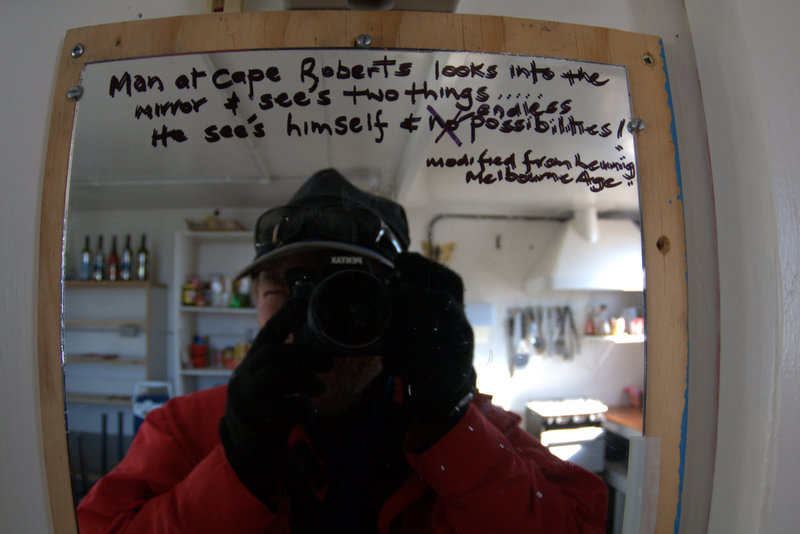

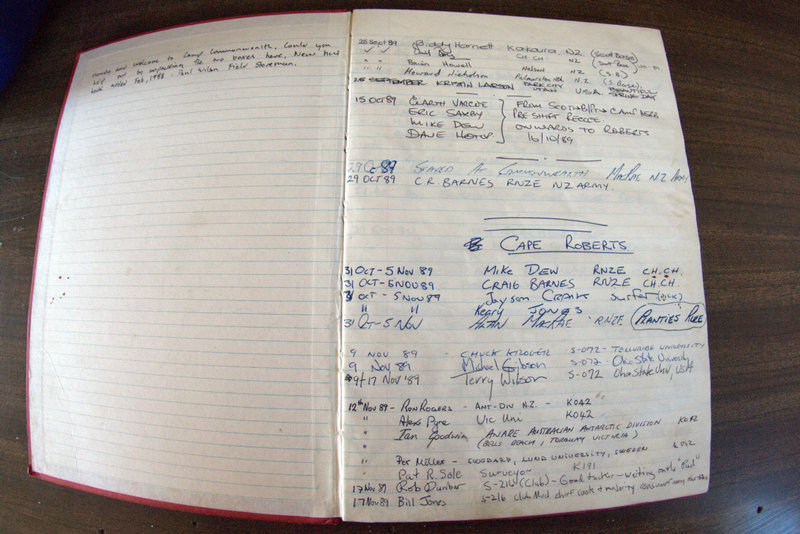

Friday was our last scheduled attempt on Cape Bird, and we had a trip up the Scott Coast to Cape Roberts scheduled for Saturday. As we lifted and headed north our view of Cape Bird was cloudless- Steve had predicted this would happen as soon as we gave up. My memories of Cape Roberts from 2001 were of a remote, wind-swept speck of land far to the north, and I remember being nervous about visiting there on a short day trip. But now long flights up the coast have become routine to our little group, and I looked forward to thoroughly checking out the area. We landed near two Kiwi huts that are maintained for tide gauge and geophysical observations that the New Zealand program initiated in 1988, and a look inside confirmed that it would be a comfortable place to hang out. We were able to quickly find our old test pits on the high terrace above the huts, and mapped the remaining pebble mounds along ridge finding no surprises from our earlier survey. I set out to walk the outer perimeter of the cape, and started near the tide gauge station. The sunward-facing cliffs along the coast were solar ovens, and I swear the air temperature there must have neared the 50s. I tried for a while to film and record the amazing sight and sound the sea ice makes as wave motion from many miles away sets it to moving, but the movement is too slow, and the sound too faint for my little camera to catch, so I gave up. The Cape proved far more scenic than I remembered- more frozen-in bergs just offshore, the massive Wilson Piedmont glacier bracketing the point on both sides, and the glacially-smoothed boulder beach resembling a Roman road sans the chariot wheel grooves. I'm finding myself more and more fascinated with fluvial processes down here, and I recorded a video of the short stream that forms from snowmelt on the surface of the Wilson Glacier and trickles seaward down the Cape. The skuas love having all the freshwater available for bathing, and their density was as high as we've seen, with several pairs dive-bombing me simultaneously as I passed through their territory. On the walk back towards the hut I found another seal mummy- although I couldn't confirm it was a Weddell since its teeth weren't visible, the dome-shaped head makes me fairly confident in the ID. As we waited for the ship to arrive to carry us back to McMurdo I looked around the hut a bit more. A log book provided many interesting stories from folks that had stayed here over the years, including a tale of recent katabatic winds that blew away the latrine, forcing them out into 65+ mph blasts while picking up the debris. Many examples of Kiwi humor and history were on display around the hut, and the bench on the seaward side was a fine spot to wait for our overdue pickup. But before long a static-laden message came across my radio- 08H was 16 minutes out. More great views of the coast resulted from the slanting sunlight, and Greg flew close to ice edge to look for whales, but they seem to be rare this season- I haven't seen one yet. Both pilot and helo-tech were apologetic about their late arrival, and had already called ahead to have meals held for us in case we missed galley hours- a very nice touch indeed. The plan for the upcoming week is more day trips, some a bit farther up the coast to Cape Ross and Depot Island, and perhaps a daytrip attempt to get to the southern-most beach at Cape Bird, McDonald Beach. I'll update again as the week unfolds.